Myanmar (formerly Burma) was the latest stop on my journey to the different Buddhist countries in Asia. I had been to Thailand (Bangkok and Chiangmai), Cambodia (Angkor Wat), Laos (Vientiane and Luang Prabang). I had also been to China and Taiwan. A few times 10 years ago, I had stood on the bridge in Northern Thailand, at the border with Myanmar, and I was tempted to cross over to the unknown and forbidden land. Myanmar was the least touristy of these Buddhist countries because it has just opened its doors and relaxed its repressive military image. (I did not see a single soldier anywhere but the reality behind the facade of peace and democracy is different, especially in the places that are off-limits up north.) It is also probably the cheapest because it is trying to promote tourism in the country.

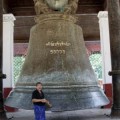

With its recent history of disasters, riding Malaysian Airlines from Manila, however, wasn’t the most reassuring in the world. But there were no other flights to Yangon available. The itinerary included Yangon, Bagan, Mandalay and Inle Lake. The transfers from one site to another required a plane ride. There was a side-trip from Mandalay to Mingun: an hour by car, an hour by boat to a village made famous by the Buddhist monk Sawaday, who is credited with making Buddhism popular in Myanmar. Ripley’s Believe it or not credits him with having a phenomenal memory because, according to a plaque, he could recite the whole Buddhist canon. It was in Mingun that I saw the biggest bell in my travels.

Formerly called Rangoon (because the Brits could not pronounce its name according to the tour guide), Yangon had the biggest Buddha at 60 feet and the most impressive temple, Shwedagon (Shwe/gold, Dagon/Big trees). Bagan had the most temples, pagodas, stupas and chedis. They were quite awesome not only for their numbers but also because they stood alone in the plains where one could see them without any other structure blocking the view. Bagan also offered the most opportunities for meditation and prayer in the temples because there were relatively fewer tourists. I did not meet any Americans; most of the tourists were

from Europe – Germany and France – and Japan.

But Inle Lake, with its network of canals and temples, was the most enjoyable destination for me. There was luckily a fluvial procession at the time, a celebration of the 5 Buddhas, and the day was spent watching different boats and pilgrims in their native attires. NB: do not forget to visit the lotus and silk weaving villages; like Bali, the weavers are trained by old artists. Many of the hotels are on the water, supported by stilts. When a motorboat passes by, the room shakes with the tide.

As in Thailand, Bali and Laos, it was obligatory not to wear shorts or abbreviated blouses and skirts in all temples we visited. Men usually donned the native longyi, a wrap like a skirt or sarong. It was comfortable to wear one because the temperature during the day hovered in the 90s. Mine was an ikat cloth I bought on my last visit to Ubud, Bali, and elicited comments from a couple of women because it was perhaps unique.

The most popular writer in the country is George Orwell whose books “1984” and “Burmese Days” are being sold openly in temples and sidewalks. (You won’t see her books in Myanmar, I am sure, but look for the works of Karen Connelly. There are books about jade, the Stone of Heaven, that will inevitably bring you to descriptions of the horrendous conditions up in the mines and the trade in these precious objects.)

Photos of the Lady appear in stores, houses, hotels, almost everywhere. The people I talked to openly expressed their admiration for her. They expect her to win in the forthcoming elections. When we passed by her villa, I asked the tourist guide if I could see her even only for a few minutes, he smiled and told me that she is too busy.