Len Roberts: Poet

It was in the mid-80s, perhaps ‘84, probably ‘85, that I first met Len Roberts. Ted Kloss, chair of the English Department at Lafayette College in Easton, PA was conducting a weekly poetry workshop and I was one of the community residents who attended regularly. One day Ted got sick and Len took his place.

I had submitted a couple of poems. One was about kite-flying with my children in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, the other was a war poem about a child in the ruins of a town in an island in the Philippines.

Len said that he liked the war poem, that writing political poetry is very difficult. After the workshop, Len told me that I should bring some of my poems to him at his office at the college. That I did. At that time, I was writing a sheaf of poems about Hiroshima. I still have a copy of the notes he had written at the time about 25 years ago. I have kept them like the other letters he had written to me over the years, mostly comments on drafts of poems I had sent him from wherever I was as I traveled the world.

Four years ago, as I packed my things to move to another house, I saw these letters again and re-read them.

These comments were not only meticulous, they also were generous and gentle. Len would ask for details, suggest another word, or hint that perhaps there is another poem sitting behind what I had written. He would say something truly encouraging and mark certain lines that he liked. There was never a time when he was cruel or nasty. And always he was thoughtful and kind.

Len Roberts and Rene in Hellerstown. Photo by Nancy Roberts.

So over a period of more than two decades, Len helped me with my poetry. I sent him and his wife Nancy postcards – from Egypt, UK, Thailand, China, wherever I was. I visited him at his house, sometimes slept over. He would get a pizza or Nancy would cook, I would bring a bottle of red wine, and the three of us would sit in the living room. One time we listened to Yoyo Ma, another time I showed a Tai chi DVD I had done and talked about my Taoist practices – Tai chi, acupuncture, internal alchemy, qigong. A favorite subject of his was his new project – building a house on an island in Nassau. Always his son Joshua was a concern. Travels with Nancy were a topic that generated much laughter. Sometimes Len and I took a walk in the backyard up the hill where he had planted black walnuts and a grove of pine trees. One night, sitting in front of the fireplace, with a bottle of wine on the table, he read his favorite poems from Thomas Hardy and DH Laurence. For the first time, I saw the other facet of these two fictionists’ brilliance.

One summer afternoon, I brought him a new poem I had written in London. Let’s think about it, he said and jumped in the pool, did a few laps, and when he came back he had a few ideas to improve my poem. Water always seemed to invigorate him: he loved the sea and planned to spend his retirement at the home he was building in the islands.

We often wrote to each other, sometimes long letters, often just short notes. We read together in the Philipsburg Art Center, NJ. Here is our correspondence about a reading the two of us did in Allentown, PA:

At 01:13 PM 3/28/00:

Dear Len,

Thank you for making me a part of that poetry reading at Borders. I truly enjoyed doing it. The tea with you and the others was fun, too. SometimesI need a break from my otherwise solitary life and the regimen of meditation, qigong and Tai chi chuan.

It’s easier now to do these things. I do bits and pieces often. I can go out at any time of the day and do a sword or spear form like it’s not really a routine but just the flow of the universe.

Breathe well!

Rene

Dear Rene,

I had a fine time, too, reading with you! One of my students who was there praised and praised your reading presence as well as the poems. Thank you

for the kind dedication at the start, also. I am touched whenever I think I have had anything to do with your fine poems.

I admire your practice and wish I could incorporate some of what you do daily into my poetry life. But the world encroaches, snares …

Hopefully this summer will open up new avenues. As well as provide time to see you here!

All best,

Len

His poetry often explored and engaged the everyday life: none of the big issues of the world but the ordinary happenings in school, at home, in his life. He wrote about the tools of carpentry, the search for the best Christmas tree in the backyard, shopping at the grocery store, doing the laundry, shoveling snow. He talked about the ordinary objects in the house and neighborhood: the gold carp, copper frog, mocking bird mobile, crickets, the periwinkle. Many of the poems are about his childhood at a Catholic school or about alcoholism, recovery, his parents and his brother. Sometimes he wrote about his early sexual experiences, which were more funny and awkward than erotic.

Even if the poems dealt with the quotidian, they were often metaphors for a bigger, larger universe or symbols of existential conflicts. He wrote about a snapping turtle that wandered in his lawn:

… his departing hiss at me a warning,

I did not take lightly,

having seen those eyes before,

and that thick shell,

that reptile brain,

knowing even as I let him go

that he would be back again.

In a memorable letter-poem, to his friend poet Hayden Carruth, who was sick and dying in a hospital, Len wrote:

… and because I know you’re close enough

to death now so you feel its breath,

its stink you’ve written so often about,

old man who used to sit at our round

oak table those blue-gray dawns

to stare out at the pond, waiting

to catch just one more glimpse

of the great blue heron flapping,

clumsy, its prehistoric wings

as it rose over the telephone wires

and trees, into the mountain

that has no name.

One of my favorite poems “Talking to the Poison Sumac” recalls his older brother who went mad, was confined to the VA hospital for 24 years and received electric shocks treatment:

And I didn’t know why I was out there

thinking of his soft body I had not held

for more than twenty years, repeating

his story when I knew that nothing

I did or said mattered, that the sky

was powerless, and the sun setting

powerless, that the snow that started

to fall, the beautiful falling

itself, was nothing, the field, the world,

the unlivable, burning stars, the emptiness

of it all contained here in one small human heart.

He did not use any big words. You understood every single word, every single sentence, because they referred to things that we know, things that are familiar, but somehow, there was something else there, something we had to decipher, something we had to translate, something much bigger than the things he seemed to be writing about.

And his long lines are something else again. You read through a whole poem non-stop, possibly in a single breath, as if the poet cannot stop the flow of his narrative, he has to take in the whole experience in one gulp. I tried the style – which my father perhaps influenced by Victor Hugo, also used back when I was in high school — and found it very effective.

The body of his work describes a life, from the grades to maturity, the slow transformation and redemption of a human being through the anguish and pain of growing up in a totally dysfunctional family, through separations and divorces, and nervous breakdowns and drunkenness, and self-inflicted suffering. Somehow, we know that poetry played a great part in that life, poetry shed light on the darkness, cleared the way for him and fulfilled the destiny that was waiting like a hidden treasure in his heart.

I look at his attainment: selection of “Black Wings” for the National Poetry Series, grants from National Endowment of the Arts and Fulbright and awards from the Guggenheim. There is also an award for his translation of Sandor Csoori’s poems. Eight books of poetry and a couple of chapbooks. Decades as a teacher. It is a solid achievement.

When I read his obit in the local newspaper a few days after his death on May 25, 2007, I was struck dumb. I was standing at Wegman’s in Nazareth, Pennsylvania, paying for my lunch, and in front of the cashier, I could not hold back the tears. My family consoled me because they knew how much I loved and respected this man. He touched my soul and my life, both, and I’ve never been the same since the first time I met him at Lafayette College a quarter of a century ago.

Len Roberts’ books

Poetry:

The Disappearing Trick (posthumous)

The Silent Singer: New and Selected Poems

The Trouble-Making Finch

Counting the Black Angels

Dangerous Angels

Black Wings

Sweet Ones

From the Dark

Cohoes Theatre

Translations from Hungarian:

Waiting and Incurable Wounds (chapbook of Sandor Csoori)

Selected Poems of Sandor Csoori

Call to me in My Mother Tongue (chapbook of Sandor Csoori)

*** The quoted excerpts are from “The Silent Singer: New and Selected Poems.” Copyright 2001 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Chicago.

Johnny F. Chiuten: Fighter

I was in the Tao Garden, Doi Saket, Chiangmai, Thailand, attending the International Congress of the Healing Tao last September 2010. Recovering from jet lag, I received the first of many messages in the evening. One was from Ned Nepangue, a friend from Cebu, Philippines, asking me to call Johnny. Then another e-mail from Vic Ramos, a fraternity brother of Johnny’s, came within a few minutes telling me that Johnny, my “old sparring partner,” had passed away. Myla Salanga, his daughter, who lives in California, sent me the same message. So did Jopet Laraya, my martial arts classmate and Johnny’s disciple, from Hongkong.

A few more messages came, confirming Johnny’s death and sending me condolences.

I am reluctant to print this photo because I avoid focusing on the fighting aspect of

self-cultivation. For more about Johnny, go to www.beta-sigma.org

The next few days I walked in a daze. I taught a couple of classes at the conference, one of them a sequence called “Twin Dragons Chasing the Pearl,” from a form – Cross Fist — I learned from Johnny in 1964.

Johnny was my first Shaolin master. He was one of the constants in my life, a great influence on my journey. I met him back in the early 1960s, a great presence in the university campus, a respected member of the Beta Sigma Fraternity. He used to come to my dorm room to teach my fraternity brother, a student of law like me. They would practice right there in the small space beside the bunk beds.

One day, Johnny and I met at the law school cafeteria and sat down at the same table. He asked me why I was not studying with him. I said I did not know that I could. We made an appointment for a lesson right then and there. It was the most important decision I had made at that juncture in my life.

On my first lesson, Johnny told me to stay in a very low horse position when we began. What he did to me for the next 3 hours or so was incredibly graphic — and painful. He kicked me, pushed me, rode on my thighs and back, asked me to walk around, slapped me all over. It was something I had not seen even in the kung-fu movies where the hero was asked to do 100 repetitions of a technique until he was bone-weary. Johnny’s method, presumably transmitted from Grandmaster Lao Kim, was meticulously sadistic in a benevolent way. I mean it was meant for a purpose, and that purpose was to test my patience, endurance and determination, and inculcate in me certain mystical values, and to build me into a warrior. Well, I don’t know if I became a warrior, but it certainly tested my patience. As for the mystical experience, I think I attained that, too, because at a certain point when I was about to collapse, I felt an enormous energy welling up, I saw a different reality, I reached a different level of awareness. I came back the next week and took some more of the same punishment. By that time, the novelty was gone, and I was ready to endure because I knew that to have a view of what it is at the top, you have to climb the mountain, by yourself.

When he graduated with a degree in pharmacy, after shuttling from one course to another to prolong his Kung-Fu studies with Grandmaster Lao Kim in Manila, he went home to the island of Cebu to run the family business. On one of his visits to Manila, he introduced me to Lao shifu, then in his 70s, and asked him to take me as a private student. The old man could not turn him down because Johnny was like his own son. It was a rare opportunity for anybody to be taught as an indoor disciple by Lao Kim, at the time considered to be the patriarch of Chinese Kung-Fu in the secretive world of martial arts in Manila.

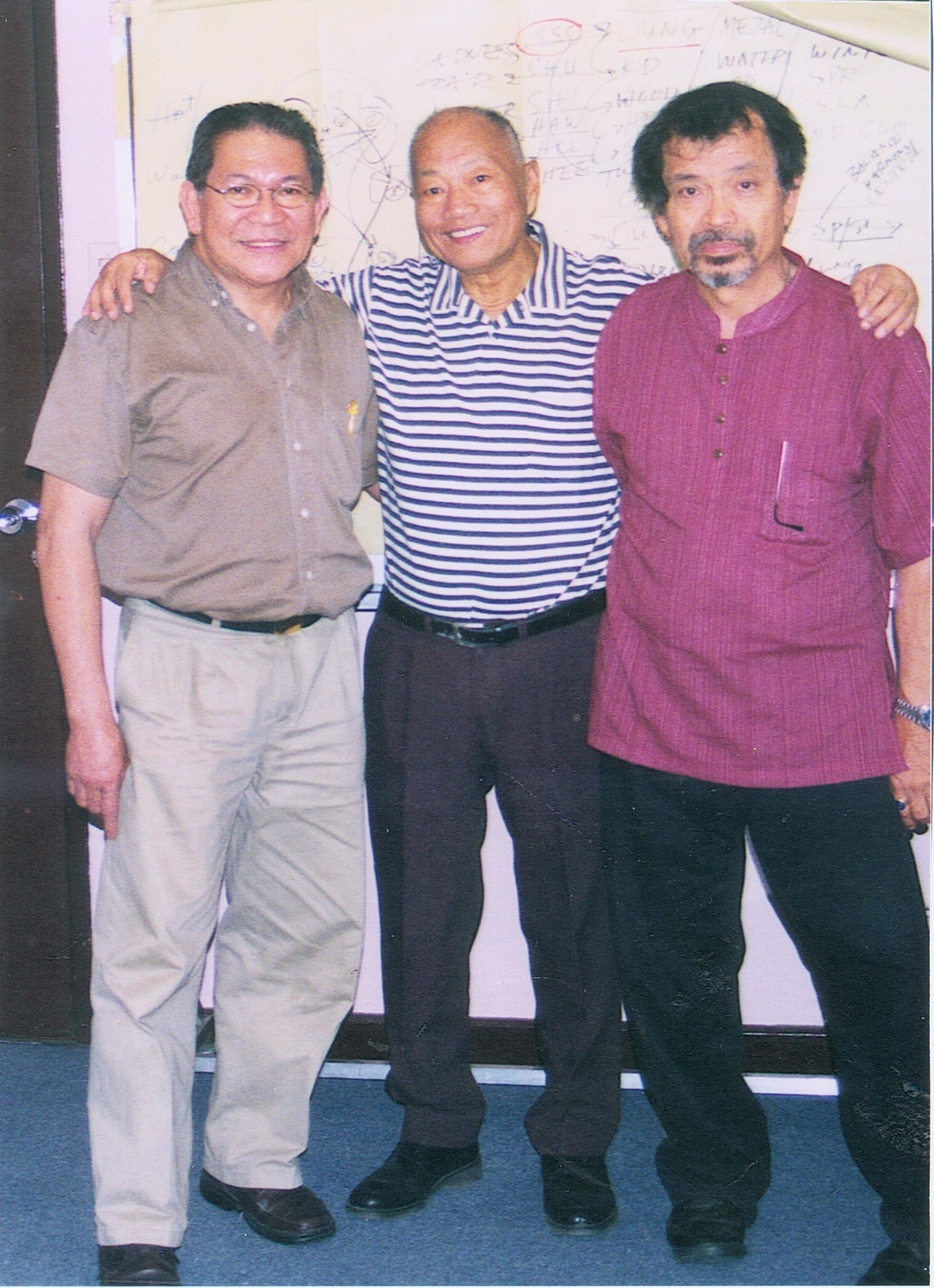

GM Johnny F. Chiuten with Dr. Jopet Laraya, martial arts

master in HK, and Rene J. Navarro, 5 years ago, in the

University of the Philippines.

Whenever Johnny visited Manila, we would get together to take lessons and have dinner with Lao Kim. Johnny would also show me his new fighting techniques. One time, he stayed in Manila for a month and he and I studied Yang Family Tai Chi Chuan and Pa-Kua Chuan at Hua Eng Athletic Club in Binondo. He learned both 108 solo form and Pa-Kua in just a couple of weeks. When I saw him again, he had added astonishing components to his system: potent jing and trapping. That’s how he was, a serious and dedicated searcher. He studied karate, kundalini yoga, Tetada Kalimasada, he was a black belter in aikido. He was into cross-training and mixed martial arts even before there was a name for them.

In late 1970, I migrated to the US. I studied with Mat Marinas, an arnis de mano/Philippine stickfighting master in Queens, NY. Meantime, Johnny began exploring the different styles of stickfighting (also called escrima) in Cebu. He studied different styles and eventually developed his own system called “Arnis de Cadena Pronus Supinus.”

There were times when yet another foreign delegation would come to see him. Johnny would make them wait on mainland Cebu while he stayed in Bantayan, an island that until recently was accessible only by land transportation and by ferry. I was with him in Bantayan in 2004 when he said how tired he was of the endless challenges he had to face in his life. But in his search he wanted to test himself against the best.

He had had several serious cardiac procedures since the mid-80s, one of them in Texas, and I did not think he should be fighting again and other practitioners should have respected the fact that Johnny’s body was no longer as supple and strong as in the 60’s and 70’s when he used to fight 4 opponents at the same time. Nonetheless, in the prevailing martial arts culture, there was no rest for the master.

Many martial arts practitioners pursued him for his combat expertise and his instructions but he never did divorce martial arts from the energetic and philosophical aspects of self-cultivation. He was always looking for techniques that used the mind and Qi without relying on the physical. He wanted to use Qi to heal himself and others. He was a fount of combat knowledge but he was also a wise man, a very rare combination in the martial world that is inhabited by many violent types and rarely by refinement. He was always respectful of others, even those who were cross and rude. To Johnny, fighting was pursued with the detachment of zen. He never did fight anybody out of anger or resentment or personal issues. In this he was unique in the martial arts world, I believe. After a fight, he usually shared his techniques with his opponent. He had an open and benevolent nature. He had a generosity and wisdom that was beyond the comprehension of the ordinary man. And he was always humble, never denigrating anybody, even those he had defeated in combat. He was a paradox in the martial arts world, gentle, thoughtful, hospitable, fluid. I could have sworn that he was a Taoist sage!

When he passed away on September 10, 2010, I lost a friend, master and guide.

Om Shantih Shantih Shantih

____________________________________

Stories about Johnny:

He told me about his encounter with a famous Filipino fighter who tried to ingratiate himself to him by taking him to places in California when Johnny was there to visit his daughter Myla and her family. Johnny expressed his doubts about the man’s intentions when we saw each other in NY while he was visiting his brother. “I do not know what he wants from me,” he said. When Johnny returned to California, the intention of the man became clear: he wanted a fight. This man was known as somebody who boasted about beating up people apparently to build the legend of his prowess. He also claimed he was a “psychic healer” and bragged about his exploits with women. As Johnny related the episode, this man said:

“Johnny, what posture will you take if I attacked you?”

“You will see if you attack me.”

The man attacked and Johnny pushed him against a wall. Johnny could have inflicted serious injury, but he used the Press technique from Yang Family Tai Chi Chuan that was partly meant to stop an attack in its track. I do not know if that was enough to bring this man back to his senses, he was not hurt but it was a shock and an eye-opener for him. Perhaps he learned a lesson from Johnny, but then again, I do not know. Johnny was terribly disappointed by the episode partly because this man tried to befriend him and abusing Johnny’s trusting nature, tried to exploit it.

Johnny F. Chiuten with doble baston. He studied different

systems of Philippine stickfighting/arnis de mano,

Wudang and Shaolin. He also studied with a grandmaster

of a Northern Praying Mantis style in HK in the 70s.

He has videos of the forms.

This second story happened back in the mid-60s when Johnny was a student in the University of the Philippines. It was late at night and Johnny had just got off the bus from Manila where he had been training with GM Lao Kim. As Johnny was walking home, he encountered a group from a rival fraternity. He was surrounded by about 30 of them. When somebody attacked him, Johnny went into what he called “ground fighting.” In this technique, it was difficult to hit him because he was down there most of the time, kicking and rolling. He managed to escape and inflict some serious damage to the muggers. Later a cop from the campus security knocked on his door and asked him to go to the police precinct. The chief told him that there were complaints that he had attacked and beat up some fratmen. But it was a charge that was impossible to prove because Johnny was alone against a big group. The charge was dropped.

The third story I can authenticate myself. In the 60s we used to spend hours doing nothing but forms and sparring. In 1966, on a Wednesday at about 12 am, it was during the Holy Week, if I remember, we had a memorable match. We had had numerous fights before, at different places. Sometimes we started at 8 o’clock in the morning and we carried the exchanges off and on until 1 in the afternoon. But this was the first time he had resorted to the technique. During a furious exchange, he stabbed my left leg and I fell. A bubble of blood formed instantly. It was one of those moments when life passes in front of your eyes. Johnny showed me how to massage the leg and put the blood back into the vein. Later, the bubble appeared again and grew to the size of a baseball. I went to see Johnny at his house in the campus. He slapped the baseball and spread the blood all over my leg. He made me drink two cups of dit da jow liniment made of 36 herbs. The recipe came from Lao Kim. My leg was black and blue for a few weeks. It was one of the scariest times of my life. Asked about it years later, he replied, “You were going to kill me. I had to defend myself.” I am sure he was exaggerating my abilities — and intention — because during the years we sparred I had never been able to touch him. I have photos to show what Johnny did, one of them I cannot publish because it shows the moment he delivered the thrust of the finger. Footnote: Dr. Guillermo Lengson, vice president of the Karate Federation of the Philippines under Johnny in the 60s, who also studied with Johnny, said of his sparring sessions with Johnny: “Sinagasa ako,” (literally translated as “run over”) referring to the technique of non-stop attack that Johnny had honed to perfection.

Shifu,

I am so sorry for both of your losses. I know both men had a profound influence on your own life and evolution. From your writings above I sense that they both knew you cherished them.

Hi Jeffrey, for a long while when Johnny and Len passed away, it was difficult for me to write. There was a void in my life. I am sure it can never be filled. One by one, it seems that the most influential people in my life are leaving. I owe what I am to them. It is like the trees that gave me shelter and sustenance have been cut down and there’s a gaping hole in the landscape. I have a responsibility to continue their teachings, to perpetuate their transmissions, and to be a worthy disciple. Rene

I understand. Continuing their teachings, perpetuating their transmissions, and being a worthy disciple is a way of both honoring them and helping them live in your heart…

Dear Master Navarro,

I am very sorry for your loss. It must have been a true honor to have known the man. I was fortunate enough this past week to have the great pleasure in meeting and spending some time with Dr. Jopet Laraya in San Fransisco. He was kind enough to allow me to join him for dinner at his fraternity brothers house, where I met some of his other fraternity brothers from the UP-Beta Sigma. I also met his sifu in Ba Gua and I can say truthfully their years of martial arts experience is very evident. My condolences to you and Grandmaster Chiuten’s family and fellow students.

Respectfully,

Micah

Hello Mr. Baxt:

Thank you for your kind comment. Despite our losses in life, and the pain and traumas we have experienced, we have to learn to move on … remembering our icons and the lessons they taught us but at the same time, living life as best we can and facing the future with joy, commitment, gratitude and responsibility. Cheers! Rene

Len was the poet and Johnny was the warrior. They stood in what seem to be opposite poles, but to me, they epitomized the human commitment to joy, dedication, and fulfillment .. in their case on the level of art: it was their common ground … and through it transcended the narrow and banal concerns of the common herd. In your words, they knew the “Art of of Flourishing.”