I sent to my friends a copy of this poem “Clearing the life,” a meditation on life, possessions and mortality, written in December of 1993 when I lived in the Case Estates in Weston, Ma, a small town just outside of Boston.

Clearing the Life

December 3, 1993, 5 am:

at the end

of the year

I try to get

my bedroom

in order. With each

day, it seems to get

smaller. It’s too

crowded now, there

is too little space

to move, I have

to tiptoe around

odds

and ends stacked

randomly everywhere. I am

clearing

junk mail, scraps,

old newspaper

clippings, notes and

reminders posted

on a styrofoam board. On my desk

are all

sorts of things: along

with my dragon chop from

Sichuan,

a Glue Stic,

slide viewer, cups, pens

that have dried,

vitamins I don’t

even take.

What is

junk, what is not?

Why do we keep some

things at all?

I’ve been looking

at each item piled

inside boxes and stuff

comes out

and feels

heavy

on my back as I

swim through

the day. Here are notes

from a previous

life. There is

a journal

from 1970 with

aphorisms,

quotes from books

I read, thoughts

on exile and my first

autumn in the US.

I know I don’t need

them, but I couldn’t

let them go

like the first

draft

of letters

on my computer.

I can’t

even remember why

they are here

buried under

other things in no

particular

sequence, each

like a claim

on my time.

I hold

this rock with veins

of crystal

and I can’t remember when

I picked it up from

what beach: it must

have been beautiful

on the surf shiny and wet;

now, it feels

warm in my hands

but yields

no more memories than

much of what gathers

dust on the

windowsill. I know

as I get older

I need these things even

less. Many that I enjoyed

before

are now dead

weights. These things

have piled

up in baskets

and drawers

and chairs

like the petty

worries

that distracted me

as I walked

in the meadow

for fresh air.

How much

do I really need

to bring with me when

my lease is up

and I move away

from here?

I wonder what

Shakyamuni Buddha

thinks

from his perch

atop my corner

bureau where

he quietly observes

my comings and goings

in this piece

of crowded

earth.

Quite

a few of these

have given me

pleasure, times

when I seemed

to descend

through

the dark and

found a

place to rest instead. A few

tell

of times

with friends who made

the journey easier, some

are maps of places

I have been to and

places I like to be. But

what do I keep a map

of Paris for

or Brooklyn,

places

I may not see

again. Some

of these things

I will give

away to people

who I hope will

embrace them as

I have like

Ursa Major and Ursa Minor,

teddy bears above

my bed. Many

of them

I will have to throw

away: rough

copies of

printouts,

those old Times

on the rack…

Make space

for my life.

12/7/93, Weston, MA, 4:45 AM

© 2022 Rene J. Navarro

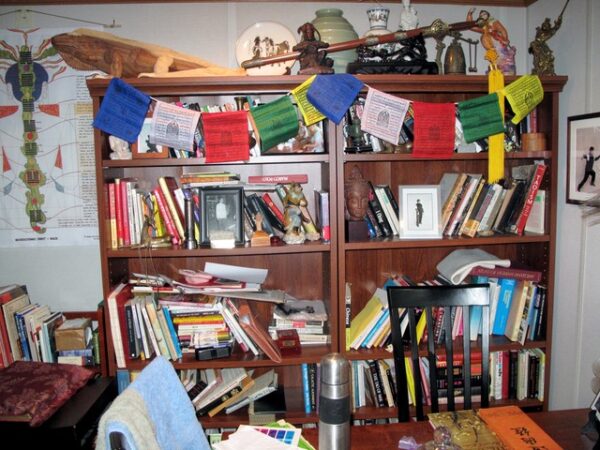

Along with the poem, I attached the photo of the Fasting Buddha in my study and the story behind it:

The Fasting Buddha Story (from “The Life of the Buddha: According to the Ancient Texts and Monuments of India” by A. Foucher)

After many stops they reached the village of Urubilva … “saw the river Nairanjana with its pure water, its descending steps, the lovely wooded shores … and the Bodhisatva’s spirit was truly charmed … and so I must settle here.” He did just that … The village still exists under the name Urel and the river now called Lilaju still flows into the Phalgu…

So it was in this peaceful and charming setting that the Bodhisatva’s frightful austerities, followed by equally terrible struggles against the forces of evil, were crowned by the final triumph of his keen intelligence sustained by an indomitable will… Many of these penances are still practiced – for instance, forced postures which stiffen the limbs; complicated fasts that follow the moon, with the number of daily mouthfuls going from fifteen to one during the dark of the moon and increasing again from one to fifteen with the new moon. There is also the rite of the “five fires,” in which the self-appointed victim sits in the center of a square formed by four burning fires, the fifth fire being the sun overhead.

Xxx

The texts show us that the Bodhisattva outdid the yogis on their own ground, the fasting ascetics, and the rishis of legend by surpassing the physical strains of the first, the abstinence of the second, and the absolute immobility of the third. First, for 6 years Gautama sat upon the hard earth in the traditional pose: torso and head erect; legs tightly crossed with soles upturned on his thighs; and hands, with palms upturned, meeting in his lap. He began by making his thoughts master his body. As a strong man might hold a weaker one, shaking and tormenting him, so his will held his body, torturing it with such mastery that even during winter nights sweat poured from his brow and armpits onto the ground. Soon he ceased breathing, and, when respiration was thus suspended, there came from his ears a great noise such as issues from a blacksmith’s bellows…

(After this sentimental interlude) the Bodhisattva began the second series of mortifications. This time he went on an extraordinary fast, eating only one grain of jujube, then only one grain of rice. And finally only one grain of millet a day. Then, with greater and greater self-control, he refused all food … the Gautama’s limbs became like knotty sticks and his spine – which could be grasped through the flabby skin of his abdomen – was like the rough weave of a braid. His protruding thorax was like the ribbed shell of a crab, and his emaciated head was like a gourd that had been plucked too soon and had withered. His eyes were like the reflection of stars at the bottom of a nearly dried-up well…

The third type of mortification again demanded that the Bodhisattva do as well and better than his predecessors. Committed to complete immobility, he did not move, either to seek shade or sunshine or to shelter himself from wind or rain. He did not move a finger to protect himself from horseflies, mosquitoes, and various reptiles. We are told that during these years no functional waste was emitted from his body. The Predestined One simply existed, his body tarnished by the elements, his senses dulled; he no longer perceived objects, neither did he see nor speak nor hear. He lost his human appearance and, still alive, he became of the earth.

An old friend, a contemporary from the Philippines, answered:

Thanks for sharing, Rene. I could relate to your meditations on life, possessions and mortality. Vic

I replied: Perhaps the problem is not the possessions but the attachment. There is life of the spirit/yoga and there is existence on earth/boga and we should learn to separate the two. But how difficult it is to tell the difference.

A friend from Long Island, New York, responded:

Dear Rene,

Thank you so much for the poem. Something in you must have sensed that is what I have decided to deal with now, clearing out all the things that I have saved, to clear out my brain and to make room for life! It was right on the money!

I also enjoyed the Fasting Buddha Story.

Thank you again! I feel inspired to really clear everything that is unnecessary out!

Be well,

G

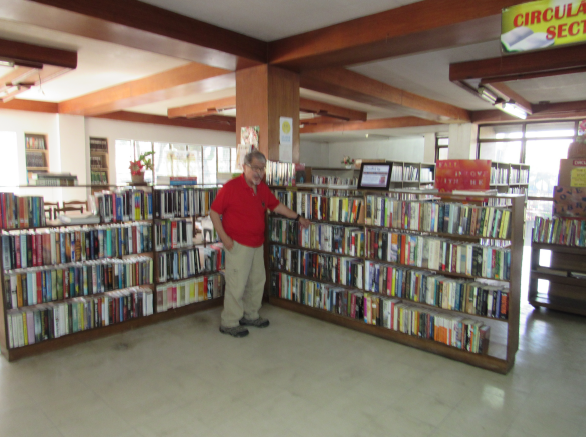

Diary: 12 3 22

I am shipping 4 balikbayan boxes to the Philippines, two of them for the Carlos P. Romulo Memorial Library and Museum in my hometown Tarlac City. CPR library already has 4 shelves of my books, most of them hard cover. I have already “bequeathed” many things: phurbas, swords and other weapons, paintings, statues (Shiva, Buddha, Guanyin). It is hard to find somebody who knows how to use a sword or what to do with a statue of the Shiva Nataraja. I gave a relative a sword and 3 years later it was rusty: he left it in one corner of the house and never even looked at it. A relative from the Philippines wanted a Buddha; she said she’ll sell it! It’s worse than seeing a sacred object gathering dust in the living room. Many people do not know the role a statue plays in life: how do you create a shrine for it? What rituals do you observe on a daily basis? How do you relate? I have met people who do not even know the basic chants associated with certain holy figures from the East or the stories behind them.

I have made a list of the other “stuff” I am planning to give away:

1. Shiva Nataraja (7 foot statue)

2. Fasting Buddha (2 feet tall)

3. Scrolls (Neijing tu, Microcosmic Orbit, etc.)

4. Swords

5. Paintings (thangka, OM, dragon, Egyptian tree of life, Last Judgment, Horses, Unicorn, Chinese, etc.)

6. Photos

7. Medals and crystals, lamps (Tiffany’s, Lion)

8. Statues (Guanyin, Bodhidharma, Rama, etc.)

9. Narda ikat (cranes) from 1986

10. Batik and ikat (from Bali)

11. Arnis Sticks ( camagong and rosewood) and walking canes

12. Phurbas, Linga, vases (one is a ceramic dragon and the other is brass with a dragon), Prayer wheels and plates (one of Xu Bei Hong’s horses, another of the Buddha)

13. Javanese Keris (reportedly from the 12th century)