The different healing modalities – meditation, qigong, nutrition/dietetics, massage, martial arts, feng-shui, astrology, sexology, acupuncture, herbalism, essential oils, alchemy – have their origins in shamanism.

I have just finished a 12-hour seminar on Shamanism and Chinese Herbal Medicine presented by Taoist priest Jeffrey Yuen. It was one of 3 seminars I have taken on Shamanism and Chinese medicine and Taoism with him. I have studied with since the millennium or a period of about 20 years now, including subjects like spiritual development, the regular and extraordinary meridians, the spiritual development of the healer, stone and minerals, the I Ching, treating traumas, including a 4-day seminar on the alchemist Ge Hong. I followed him in Boston, Maryland, North Carolina and New Jersey. At the seminar on shamanism, he talked about the paradigm of the human body, the role of the shaman, the different herbs (mineral, animal, and plants) used, the quest, journey and rituals, the opening of certain energy centers in the body and the meditative and self-cultivation methods. Apart from those, he introduced his subject by saying why the popularity of shamanism has diminished in China: partly it was because of the Communist regime and its policies. He did not really spend much time on this issue but it made me think of why shamanism in my country has been pushed or forced to the periphery of our culture.

It is important to understand what a shaman is. There are usually equipment and paraphernalia involved like feathers, crystals and stones, drums, chimes, rattles and ritual clothes, cymbals, bells, water and fire, essential oil, staffs or even swords, and masks. A Hindu healer in Bali who treated me used a stick shaped like a snake to poke at certain points in my body. He chewed on some herbs, one of them I recognized as Sichuan peppercorn, and spat it on my face to treat me for a sinus congestion. Another shaman, who was also a Hindu priest, taught mantras and mudras as part of his repertoire of healing and self-transformation methods. He had a pet gecko on the rafter of his house. Aside from actual healing methods, there is also chanting and trance dancing. S/he is a combination priest, shaman, healer, usually an elderly person, who has been trained in the arts of healing and rituals, a kind of bridge or intermediary between heaven and earth, the human and the divine, the lower and the higher dimensions. I met a shaman in Peru who studied with her grandmother. So, the tradition might be perpetuated in families, perhaps on the female line. Another shaman, who was also my guide in Peru, studied in the jungle and was initiated with the psychotropic ayahuasca. But psychotropics are not always included in the rituals. There are shamanic traditions that use fire as part of their healing. One shaman in Bali (he was also a Hindu priest) used a red hot chisel on my tongue; he “touched” the back of my tongue 9 times in a row and then told me to dip the chisel in a glass of rose water, after which I used the water to wash my face. We did it 3 times that night. The next night we came back for more. In the East, Fire Walks are a common experience. I’ve seen it in Bali many times. It is also done in some villages in the Philippines.

We did this ritual 3 times that night. We returned the following night to do it again.

Beyond the equipment and the rituals, there is the nature of the shaman. What she is and what she believes in. The shaman is a bridge between this and that reality, between the material and the mystical. As a bridge, she is composed of a different energy and highly developed senses and intuition so that she could access different vibrations and frequencies. Her senses and intuitions could reach beyond the ordinary world. She has instincts that could “see” and “feel” different manifestations of reality. She has senses that could detect things that the ordinary individual does not even suspect exist. What did the shaman have in ancient times – abilities that have been lost or forgotten? Some animals could feel or see the coming of a storm, the bats could “see” in the dark, the trees could communicate with other trees, some insects could detect a calamity. Even some dogs could “smell” anger or a negative emotion.

In my experience, the shaman has a connection to the animist world – the world of nature spirits. She communicates with them, secures their help and guidance in her work and in healing and acknowledges their assistance in acquiring or developing abilities and powers. She engages in divination, sometimes using the I Ching. I heard practitioners say that they were guided by their ancestors, immortals, saints or sages, that they received secret transmissions from them. A woman in Bali reportedly acquired the power to emit “electricity” one day as she was praying to Guanyin, the Goddess of Mercy. She was able to learn how to control it and used it for healing. Eventually, her husband acquired it, too, and the two of them began healing together. I experienced their healing power in 4 sessions in 2 pilgrimages to Bali.

The ancient shaman had a developed consciousness, partly through training and self-cultivation, partly through the legacy of a culture that included the “other world”. I have met shamans who could emit some form of electricity, move objects from a distance or project intense heat from their body or hands. In Bali one psychic from Russia demonstrated her ability to read a book with her eyes blindfolded.

Probably the most important shamanic discipline I studied were transmitted by Mantak Chia, the grandmaster of the Universal Healing Tao that is now based in Chiangmai, Thailand, although it has branches around the world. His core teachings came from Yi Eng/One Cloud, a hermit from Central China who, during the Second World War, escaped the bombing and moved to the New Territories in Hongkong. It was there that a classmate introduced Mantak to the hermit and where the young high school student studied the Transmissions of the Enlightenment of Kan/Water and Li/Fire, or the 9 Levels of internal alchemy/neidan. These were ancient shamanic practices of immortality that were, until then, kept secret. In the late 1980s, GM Chia asked me to write the texts of the levels. I attended his seminars at Rudi’s at Big Indian in the Catskill Mountains in Upstate New York in the summer and wrote the procedures based on his teachings. He gave me hand-written and typewritten notes and videos. I had already assisted him in the summer retreats and was familiar with the foundation courses but here, for the first time, I encountered an entirely and absolutely different terrain. I wrote and/or edited the materials and came out with 3 manuals: Lesser, Greater and Greatest Enlightenment of Kan and Li. At the millennium, after attending the retreat and assisting him in teaching Kan and Li, I also edited the last of his public teachings on alchemy, Sealing of the 5 Senses, which happens in the Upper Dantian.

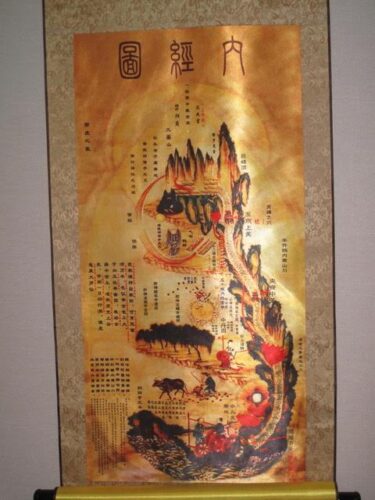

I discovered that many of the Taoist principles and practices had their ancient roots in shamanism. You could see it in Taoism’s cosmology of the human body and in its different principles and practices. The foundation meditation called Microcosmic Orbit/Small Heavenly Circle/Xiao Tian Zhou, Buddha Palm Taoyin, the Fusion of the 5 Elements and the Enlightenment of Kan and Li are shamanic practices. There are others, including books and manuals by the masters: the I Ching, Dao De Jing, Zhuangzi, numerology, acupuncture, herbalism, divination, meditation, alchemy, astrology, feng-shui, etc. The early shamans knew the alignment of the stars and the seasons, the time of planting and harvest, anniversaries and celebrations.

When I was growing up in Bamban in the 1940s, there were a few hilots and herbolarios who carried on the traditions of the babaylans and the kuranderas. There were other names for these healers in different regions of the country: mangngagas, manguru, managtambal, manulu, manggagamot, parabulong, manugbulong, mananambal, tambalan, mangungubat, pamomolong, taligamot, kurandero;mumbaki, babaylan, binungbungang babaylan, balyan, manpokus, mangangalap, magtatawal, mangagon, gemot, pegkamal sa kapenggamot, libun mulung, libun mewa nga, libun tamlo loos, gmemalung, and others, according to the list provided by the Deklarasyon Tuguegarao sa Gamutang Pilipino.

They were part of the worldwide phenomenon of traditional healers who used incantations, rituals, herbs and prayers to heal and to communicate with the “other world” of the divine and spirit.

When I had an injury – a pulled muscle or displaced joint – I would be taken to the local healer during my childhood. He or she would apply a hot oil and/or a leaf and chant some words. I did not remember what the process was but I felt that healing happened and I felt better. For many years, when the family moved to the capital, I missed these healers. In 1986, when I was was studying Lapunti Arnis de Abanico in Cebu City, I was introduced to a healer whose name was Domingo Lapurga. I spent several hours at his clinic. There were about 20 “patients” there waiting to be treated. One of his techniques was to flick his index finger from 2-3 feet away and an incision would appear and blood would flow on the very spot where there is swelling or inflammation. He did not use any knife or scalpel. He would then put a coin over the cut and a cotton ball with alcohol, light it and cover it with a cup. The vacuum would draw the blood out and the treatment was done. During the time I was there he did it several times on different patients, a couple of them Japanese. There was a young woman on the table with a growth on her breast lying on the treatment table; he asked me to flick my index finger over her. I did and was surprised to see that there was a cut on the growth on the breast of the woman.

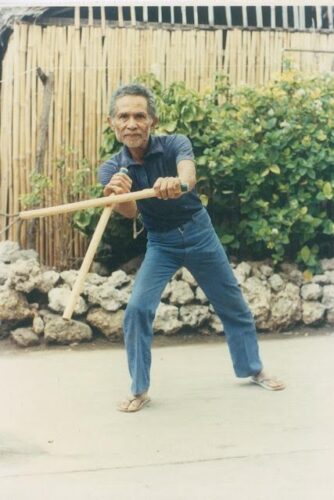

When I was in Bantayan Island, I studied with Guillermo Tingga, an arnis de mano master. He was also a native healer. His method was different. He had a crucifix hanging from his neck: it was known as the martial artist’s amulet, with a crucified Christ on each side of the cross. Sometimes he would pass it over the patient’s body, but he also used touching and orasyon (prayer or chant) and a sprinkling of water. When I went to see him during the Holy Week in 1987, he was not around. I was told that he was spending a few days up in the mountain in the next island to commune with the spirits of nature. That says a lot about the shaman’s connection with the environment.

When I attended a conference in Baguio City, I was taken to a healing session. I had a problem with my knees and back, probably due to a Winter month teaching in Amsterdam. An old woman was assigned to treat me. She applied coconut oil on my lower back, slapped a white paper on it and as she pulled it off, there were squiggles on it: she said that I suffered from wind and cold. Then she passed her hands over my back. I felt warmth. The pain was gone and I was pain-free at least for sometime.

These experiences – in Bantayan, Baguio and Bamban – were a few of my contacts with Philippine healers. I had also met with healers in Mount Banahaw, the first time in June of 1986, and in Manila (one of them a psychic surgeon) in the millennium. For those who are looking for the ancient babaylan, they’ll find them in different places, but most probably, they’ll see only the remnants of the tradition. Like the hilots and herbolarios in my hometown in Luzon, these healers carry only a few of the methods from the ancestral shamans. What happened?

As in China, there are reasons why shamanism has been diminished or forgotten in the Philippines. Part of it is the introduction of western medicine, values, knowledge and culture. Another part is the influence of the Roman Catholic Church and Christianity in general. And of course, there is the modern skepticism about these ancient beliefs and practices.

There could be a revival of shamanism if there is a deliberate research into and study of its traditions and rituals. There are probably going to be obstacles to it from religious individuals and institutions and the modern culture that is more and more materialistic. And how do you address the conflict between institutional religious beliefs, on the one hand, and folk and tribal shamanic customs, on the other? And since many shamanic principles and practices are possibly dying or dead, how do we revive them? One practical solution is to closely study and then adopt similar principles and practices from other, perhaps neighboring countries, where they apply. There are, after all, many similar traditions in countries like China, Mongolia, Siberia, Thailand, Indonesia. Some of their healing arts and rituals have already found their way into the Philippines. Acupuncture, massage (shiatsu, tuina, Chi Nei Tsang), martial arts, cuisine, meditation, herbalism, moxa, etc. are becoming more popular even in remote places as far as Davao and the Ilocos. There are already schools teaching them. There are also Filipinos who have formally studied Taoism in China; they will eventually bring not only their knowledge of academic theories but also actual practices home and share them in the schools.

For a long time scholars and academics have taught the “philosophy” and theories of eastern religions. Taoism, for instance, was approached from an academic point of view.

Lacking was the actual practice of self-cultivation. There was a time when Tai chi chuan, feng-shui, meditation, qigong, and massage, among the healing modalities, were discussed as theories but not presented as regular practices. When Michael Saso (Hawaii) and Kristofer Schipper (Netherlands) did their field work in Taiwan, they were ordained as Taoist priests and they brought the monastic rituals back to the West. Many Buddhists have also come out and began teaching different facets of their religion. Phowa, Yoga of Dream and Sleep, and Tummo, among others, from Tibetan Buddhism are being taught more openly than before. The Taoists are teaching their practices and holding Darkness and Internal Alchemy Retreats and Bigu, a form of fasting. We can go on providing a list of various eastern disciplines that are now standard teachings in temples and center around the globe.

It is easy to imagine that that this phenomenon will impact the world.

NB: There are several books on shamanism in my library but

two of them stand out: Mantak Chia and Kris Deva North, “The Taoist Shaman:

Practices from the Wheel of Life” and

Richard Herne, “Magick, Shamanism and Taoism.” There are also videos you could google online

on the shamanic and healing traditions in Korea, Japan, Mongolia, Siberia,

China and Mongolia. Here is one from the Philippines:

https://youtu.be/lLv7ldIB4vc

For those who are interested in ancient Philippine materials on astronomy, there is the book “Balatik Etnoastromia: Kalangitan sa kabihasnang Pilipino” by Dante L. Ambrosio (UP Press 2011)

For a background on the Keris, see the link: https://youtu.be/uUBIkjRgO9c