Why Tai Chi Chuan and Chi-Kung? A Journey into the Paradigm of the Human Body in Chinese Medicine

By Rene J. Navarro, CA, TCMP

Thank you for inviting me to this convention of the Philippine Academy of Acupuncture. I remember that a few years ago I taught Qi Nei Zang internal organs transformation massage to the Academy organized by the resourceful and indefatigable Janet Paredes.

show moreAs I look at what’s happening in the Philippines, and listen to the varied stories, I can’t help but comment that there’s a phenomenon here of a market situation with different people and groups seeking recognition and acceptance for their approach, modules, techniques and protocols. It is a phenomenon that recalls the situation in the US when acupuncture was introduced and taught in schools: there was a kind of rush to be a part of the mainstream, a move to be taught in schools and institutions: massage, meditation, yoga, styles of acupuncture, dietetics, essential oils, crystals and stones, qigong, etc. There were at one time more than 50 schools in the mainland United States; in Hawaii alone, there were 3 Oriental medicine schools; in the New York area there were I think 5 schools, 4 of them located in Manhattan.

And then, to top it all, there were companies that supplemented this unprecedented growth: they manufactured and/or imported and sold equipment: paraphernalia like needles, electro-acupuncture machines, pain relief pads and pills, different herbal formulas, lotions, tonics, etc. Perhaps it was not all for the money but the healing profession with a mission to spread a different healing modality became big business. Even western allopathic doctors, nurses and therapists jumped onto this new Oriental Express. For a period of time, they were the group that dominated and controlled the profession as the acupuncture schools proliferated. But this year, about 50 years after the recognition and licensing of acupuncture by the states, some of the schools are closing partly because there are not enough students to keep the schools open. The US was so saturated with schools of acupuncture that the market could not muster enough students to keep them financially viable. One school in Hawaii, where I was teaching Qigong, closed as early as the millennium because there were only 4 paying students! My own acupuncture alma mater, the New England School of Acupuncture outside of Boston, got absorbed by a western medical school because it could not stand on its own financially. A prestigious Oriental medical school in the Western US closed just recently. Another school outside Washington, DC closed too almost simultaneously. Perhaps that tells us what the future is for acupuncture and other healing centers in the country. As I look around me, even when I drive from one town to another, I can see massage centers, many of them selling bodywork from Thailand. Back at the millennium, there were a few Filipino women studying traditional Thai massage in Chiangmai. Healing has indeed become just another commodity to be sold in the market!

To get to the subject of my paper: As far as I know, no single book or website has fully explained the many wonders of Tai chi chuan/Taijiquan. Many haven’t even come close. There are many possible reasons. Perhaps it is because the masters approach the art from one (or two) limited perspective, do not know (or did not learn) the art in its entirety or, because of the prevailing secrecy in the culture, have chosen to explain only one or two aspects of it. Perhaps also the public asks for lessons in Tai chi chuan only to learn the movements or as an exercise.The same is true of Chi-Kung/Qigong.

One problem is that “body and mind” are actually very limited and vague concepts. Moreover, the western body and mind are different from the eastern body and the eastern mind. “Xin” showing a heart in Chinese, is translated poorly as “body-mind”. There are many scholarly commentaries about this subject written by academicians. (Harold Oshima, “A Metaphorical Analysis of the Concept of Mind in the Zhuangzi,” Deborah Sommer, “Concepts of the Body in the Zhuangzi” in Experimental Essays on Zhuangzi edited by Victor Mair.)

One possible drawback is that Tai chi chuan and Chi-Kung have a different paradigm. If you are studying western medicine, you have the kind of body you are working on, there are the methods to address that body, you have the tools. Basically, the western approach to medicine is like the approach to a machine (the body). The eastern approach is more holistic: the eastern body is not just physical, it is energetic, spiritual and there are principles that govern its functions (qi, Yin Yang, Wu-Xing, meridian and organ system, the concepts of shen, prenatal and postnatal energetics, San Bao, polarities, neidan/internal alchemy, etc). These are two different paradigms, although western science is now beginning to adopt eastern premises and methods and vice versa. There are books explaining this difference (Ted Kaptchuk’s “The Web Without a Weaver” and Liu Yanchi’s “The Essential Book of Traditional Chinese Medicine”). Many people who practice Tai chi chuan and Chi-Kung do not even have half a comprehension of the profound and multi-faceted arts they are dealing with. The public especially see it sometimes only as a slow exercise for old people in the park or for people with certain disabilities.

To work with an art, like acupuncture, herbalism, qigong and internal alchemy, or painting and sculpture, you have to understand what you are working with: your materials and instruments. If you are playing the cello or the piano, you have to know the vocabulary of your instrument, its possibilities and techniques. If you are a poet, you would have words and rhythms and images, allusions and conventions of the art.

The same is true of Tai Chi Chuan and Chi-Kung. You have your body as an instrument. It is your means of expression. With your intent/yi and movement, you can tap into your body’s varied potentials –– to bring out what you are capable of.

So what is the nature of your instrument? What are its potentials and possibilities? What can you do with it? What “music” can you play? There was a time when the human being was divided into the Cartesian body and mind, each one with its own territory separate from the other. Nowadays there is a different division or combination: Mind-Body-Spirit. But it does not capture the totality of the eastern Taoist/Daoist paradigm.

Let me list a few things that are the components (physical, intellectual, emotional, energetic and spiritual) of the body from a Taoist Eastern point of view:

Muscles,

Tendons

Bones and of course, the bone marrow

Fluids and the blood

Hormonal, lymphatic

Organs and their different features (colors, senses, sounds, elements, seasons, functions, etc.)

Meridians, among them, the 12 Regular and 8 Extraordinary Vessels

Mind and Heart

Qi/Chi

yin and yang

5 elements: metal, water, wood, fire and earth; colors. Flavors, senses, animals, colors

Prenatal and Postnatal energies

3 Treasures – Jing, Qi and Shen – San Bao

3 Cauldrons/dantian and 3 Burners (lower, middle, uppers)

Dantian or the hara, the Moving Qi Between the Kidneys (MQBK)

3 Shen/Spirits and 7 Ling/Souls

Last but not least, the Ming Men/Gate of Life

All of what I have mentioned will come into play in Tai Chi Chuan and Chi-Kung later, if you have the passion for the art and if you have a good teacher. The question that comes to mind is, How do you activate or trigger some of these eastern body parts? For instance, the meridian jing/well points or the yin-yang in its many aspects? How do you work with the bones and the bone marrow? How do you build the dantian, the Elixir Field? How do you develop fa jing/discharge of jing in its 34 or 35 transmutations? All of these are an integral part of Tai chi chuan, at least in the authentic Yang Family tradition.

Do we even know what the Dantian refers to? What are the jing, qi and shen? How about Hun, Po and Shen and the 7 spirits? Where is the Ming-Men really located? How many acupuncturists and TCM practitioners have actually studied and practiced a meditation on the 12 regular meridians and 8 Extraordinary Vessels? What do we bring into our different practices?

Which of these components comes into play in your practice of the different healing modalities, whether it is acupuncture, massage, essential oils, stones and minerals, martial arts, feng-shui, astrology, Tai chi chuan, chi-kung, sexology, nutrition, dietetics and alchemy?

When your hands are on your side, palms facing the back, what is it that you are actually doing? Then, what are you doing when you are turning your palms to the front and raising them like so to the shoulder level; then you are turning them over and bringing them down back to their original position at the level of the thighs?

Tai Chi Chuan, like Chi-Kung, is movement of course but it is also much more. Here at the beginning you are aligning Hu Kou/LI 4 to the GB meridian, you are sensitizing and feeling the back with the palms. As you are turning your palm to the front and raising them, you are following the first hexagram of the I Ching – Heaven. You are activating the Jing/Well points and the Lao Gong/PC 8 and the Dantian/Field of Pills, you move and cultivate the qi, you make the bones and marrow “breathe,” you pack the Qi into the dantian, you activate the meridians. And then you turn the palms down at shoulder level and bring them down following the second hexagram Earth/Di. These simple gestures take time to explain, I’ve actually skipped a lot of information because I only have 20 minutes for this paper. And I have not even touched on the other fist and weapons forms – Push Hands,

2-man sparring set, the Great Puling/Ta Lu, the rare Tai Chi Chuan Chang Chuan or Long Fist, the staff-spear form, 3 Dao/Broadsword forms, and 2 the Jian/Straight sword forms.

You have to know the relationship of the different energy centers and points so that you can connect them in a pattern called Sacred Geometry, so that there is Gan Ying/Resonance. There are “points” in the body that connect to the external and internal world. The Bai Hui/GV 20 connects to Heaven, Yong Quan/KD 1 connects to the Earth, Stomach 25/Tian shu connects to the Big Dipper, the Lao Gong that gathers and emits Qi, the finger tips and toes that gather and emit Qi, etc.

You have to know what the human body is all about. That will show you the possibilities of the art.

Learning Tai chi chuan or Chi-Kung is analogous to building a house. You build the foundation first: that’s comparable to learning Zhan Zhuang, the stationary postures or standing meditations that are basically the basic structure of the body. Then, you build the walls and the roofs, the equivalent of the arms, the feet and the triangle bones. After all the material structures are put in place – the kitchen, toilet, bedrooms – you lay down the power sources, the grid of energy: wires and the lights. These are like the dantian and meridians of the body.

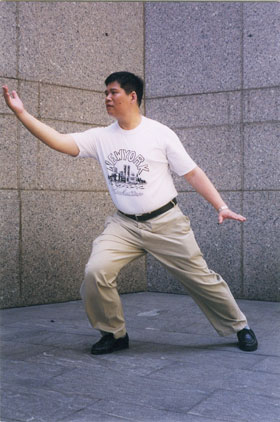

I started studying Yang Family 108 Tai chi chuan fist form at Hua Eng in Binondo in 1968 in the Philippines focusing on a form taught by Master Han Ching Tang of Taiwan and in 1970 studied a different version of the 108 with another Taiwanese master Liu Yun Hsiao. In 1978 I studied Wu Tai chi with Master Leung Shum in NYC. And then while studying acupuncture and herbs at the New England School of Acupuncture in Boston in the 1990s I trained for 10 years with the Yang Family master Gin Soon Chu: this was the complete curriculum of the Yang Family that included the 108 solo fist form, medium frame, tiger style; staff-spear; two forms of the dao or broadsword; two forms of the jian/straight sword; da lu or Great Pulling; Tui shou/Push Hands; San shou/2-man sparring; and Tai chi chuan chang chuan or Long Fist. I can truthfully say that this curriculum is the most complete in the world. Compared to the authentic Traditional Yang Family curriculum, the modern, Communist era Simplified Tai Chi Chuan forms are indeed a poor relative.

But perhaps I began to see the other aspects about 30 years ago when I was in acupuncture school and was writing the books on neidan, internal alchemy, the Enlightenment of Kan and Li/Water and Fire for Mantak Chia, grandmaster of the Universal Healing Tao. The paradigm is an essential step to understanding. This makes an important ingredient in our progress in Tai Chi Chuan and Chi-Kung. I also studied Tai Chi Chuan and Chi-Kung with him, along with sexology, and the Tendon and Bone Marrow Classic.

One thing too that we have to remember is that the legendary founder of Tai Chi Chuan was Zhang Sanfeng (Zhang of the 3 Peaks). He was a monk in the Shaolin Temple in Loyang for 10 years in the 10th or 12th Century of the Current Era, apparently studied Damo’s Yi Jin Jing/Tendon qigong and Bone Marrow Washing Classic, part of the Lei Shan Dao/Thunder Path lineage. The Immortal Zhang wandered China studying with masters and finally settled on a peak on Wudangshan, the Daoist sacred mountain retreat. There he choreographed Tai Chi Chuan after seeing (or dreaming about) the fight between a Snake and a Crane (incorporating the dialectic of yin and yang). Some of the transmissions of Zhang – like the 13 movement Tai chi chuan and the Yi Jin Jing –have survived and are being taught.

But I suspect that there are valuable pieces that have been kept secret by the masters, some of them the hermits I met in Huangshan and the Magus of Java and others.

Finally, we have to understand that what we are doing is not just an exercise, although it is good as an exercise. What we are doing is not just martial art, although martial art is good. What we are doing is not just movement, meditation, qigong, dance, alchemy, centering although Tai Chi and Chi-Kung are all that. We have to see the perspective of its mythology, its archetypical aspect, and our place in the history of the art. Tai Chi Chuan and Chi-Kung came from different legendary sources – shamanism: our connection to heaven and God or the gods and goddesses; eschatological: our relationship to ultimate issues; our body as a part of the universe, as a link in the continuum of energy/qi. As below, so above; as above, so below. There is no separation or disconnect between us and the environment. In the modern world, we seem to have lost this key. We treat nature and the earth as alien or, at best, something to be dominated and exploited. We treat our bodies only in the physical and material level.

Sadly, when the Communist government took over in 1949, they brought with them a materialist ideology to China and imposed their ideas on the country. Healing modalities were made to conform to this ideology – acupuncture, chi-kung, martial arts, etc. We saw practitioners of chi-kung being arrested and tortured and killed for promoting Qi-oriented and spirituality-directed practices. Martial arts were re-choreographed and revised by a committee. These revised principles and practices were also exported to other countries. I studied it at the New England School of Acupuncture in the 1990s. I also studied the wu-shu aspect in Chengdu, Sichuan, in 1983.

We have to take Tai Chi Chuan and Chi-Kung as a form of worship, a ritual of reconnection to our origins and to the divine. We need something like it to bring back the sacred in our lives. Through movement of the fingers we are reviving our sense of touch, our ability to feel the world around us, something we do not see or hear or smell or taste.

We have probably lost this extra-sensory perception while other animals have retained theirs: the bats can “see” in the dark with their ears; dogs can smell from a distance; salmons can “remember” and find their way back to the water of their birth; some birds can track their way in their ancient migration; even trees can detect the coming of a storm and they can communicate it to each other in their own vocabulary and language. The name Tai Chi Chuan has been translated into English as “Grand Ultimate Fist” which indicates its depth, magnitude and power. The pinyin transliteration is Tai which means great, Ji means the extreme (different from chi/qi or lifeforce) and Quan or fist. If you look at the characters, especially of the first two, you’ll see that the English translation is inadequate.

There is really nothing like the actual practice of Tai Chi Chuan to feel its effects. No explanation can capture the bliss and the power generated in the course of a long workout. Words, as the eastern expression puts it, are just the finger pointing at the moon. Chi-Kung is likewise a very much misunderstood art and practice. The character Qi – steam rising from the field of 8 directions — indicates the cultivation of the mystical Qi/Chi in the body while Kung or Gong – with the characters Li for strength and the carpenter’s square– tell us that we have to do it, not just for a weekend but over a long period of time. Whether it is Tai Chi Chuan or Chi-Kung, the road is long and hard. The different ingredients involve a different body, not just physical but also mental, energetic, shamanic, spiritual. The whole paradigm of the body from the eastern point of view.

show lessPilgrimages

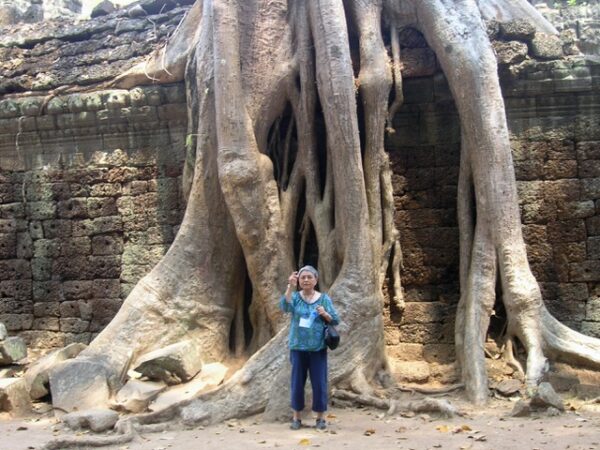

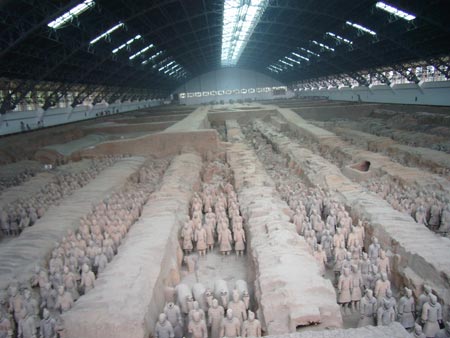

One of the things I miss is traveling to distant countries. Not only remote countries but sacred places. Every now and then I would look at my archive of photographs and revisit them: Borobudur in Indonesia, Angkor Wat in Cambodia, Glastonbury in England, Lake Titicaca and Machu Picchu in Peru, the stone circles of Scotland, Mount Banahaw in the Philippines, the stone house of Mother Mary in Ephesus, the Oracle of Delphi in Greece, the basilica of the disciple Lazarus in Cyprus and the pyramids of Giza in Egypt.

show moreI am not a good travel writer. I do not bother to point out ordinary places no matter how attractive or give directions to tourist spots. I am more interested in places of pilgrimage where I could feel a special energy, discover the divine presence, an insight into myself or life, or find an extraordinary experience that will transform me. There are many such places in the world.

But it requires a special kind of listening, patience and curiosity to “connect” to the special energy of a place. Perhaps, if you’ve done meditation, Tai chi chuan or an art like painting or poetry or you have a religious calling or love history, you’ll be able to feel the frequency or vibration or if you have the ability to keep quiet and allow the atmosphere to enter, you may be able to access the “heart” of the place. You have to leave most everything behind and be open to a new experience. In the phraseology of Zen, you have to empty your cup to get it filled. That is a precondition almost of how you build an energetic relationship with the place.

Often you have a background knowledge of the place you are going to because you have read about it in your research. But it could also be that you do not know where you are going because a guide has it all planned for you. This was what sometimes happens when only an outline of the tour is provided. It has happened to me more than once. On a trip to Myanmar, my companion and I were picked up from the hotel by car and were taken to a boat. We did not know where we were going. After an hour, we arrived at our destination. We walked to an old temple built into a cliff. It had a small, bare altar inside, hardly big enough to accommodate 10 people. There were 2 monks. And then the guide took us for a walk to a white temple. We had the same kind of experience when we were in Laos: a guide took us from the hotel, put us on a boat on the Mekong, and after 2 hours, we clambered up a a ladder to the Temple of 10,000 Buddhas.

In other counties it was different. We had no guide to lead us. During a pilgrimage to Delphi I took my two granddaughters Ava and Isabel with me. They were a great help with navigating the mountain: My primary doctor allowed me to join the Mediterranean tour although several tests showed I had symptoms of a heart condition and a cardiac procedure was considered a possibility. I let Isabel and Ava to go ahead of me when I reached the plateau. I sat down and did my qigong overlooking a breath-taking landscape. It was Summer Solstice, June 21, and there were women in white tunics chanting probably in honor of Gaea, the Goddess who was the original Oracle before, as in many other places, the patriarchy installed a man – in this case Apollo — in her place.

Sometimes the destination is not the place but a master. This was true in my visits to Bali, Java and Huangshan. I was with David Verdesi; we went to see “King” (I do not like to disclose his name to preserve his privacy) and a 93-year old Hindu priest famous for his ability to change into a monkey right before your eyes. King gave us a rather strange initiation – passing a red-hot chisel on our tongues. It was a cleansing and kundalini ritual. Another master David took me to was the Magus of Java, the legendary John Chang who could project electricity from his body. And of course we went to Huangshan to meet with GM Kong and Feng shifu, both wonderful healers with powerful energy and generous spirits. Important to remember: Whenever you meet a master, it is important to be humble and sincere. The master invariably can “read” your energy at first sight and it’s possible you’ll be ignored or told to return in five years.

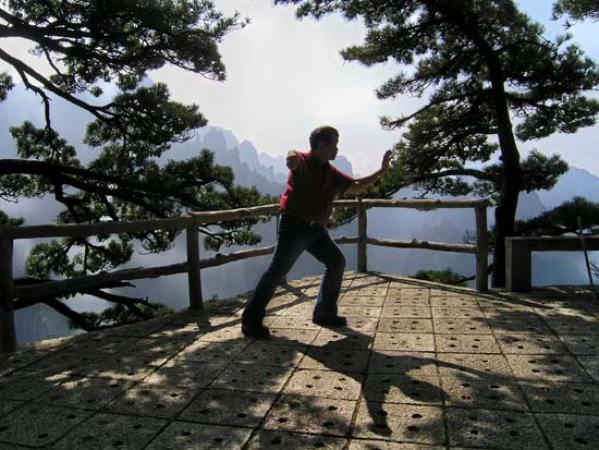

I’ve done my meditation rituals or, when possible, Tai chi chuan in different places: Avebury (an even larger and more extensive stone circle than Stonehenge),Temple of Karnak (where Jesus spent some years studying with the priests), several places in Scotland, and Besakih (Mother Temple) on the slope of the volcano Mount Agung in Bali.

It is difficult to explain the experience that is spiritual and mystical. There is a kind of transfiguration, a heightened sense of wonder, a departure from the ordinary and mundane. You leave the place transformed and you are aware of the possibilities of life and travel. This experience is totally different from mere tourist travel. In the latter you are just a casual visitor, you see things – however beautiful or impressive – but they do not affect you in a deep sense, you are not transformed emotionally and psychically, you do not establish a profound relationship with the place or the person you are seeing.

When I walked up the Tor in Glastonbury, I felt myself on some kind of initiation, walking along not just a path but a Path. Step by step, I was being suffused with energy of the place and its history, I was actually moving into the past or the mystical, beyond the geography or the location, beyond into the mystery.

That is the apotheosis of a pilgrimage. You are touched on a soul level and you are not the same again.

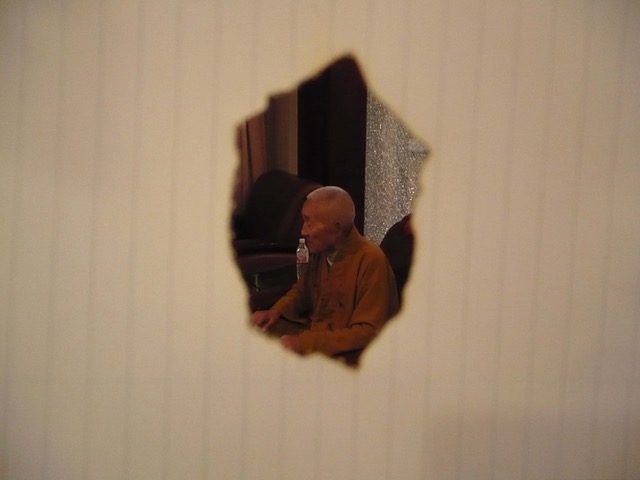

Huangshan is considered the most beautiful mountain range in all of China. It covers miles of awesome landscape. I visited Huangshan two times, once with my partner in 2005, the other time in 2007 with a group that was guided and taught the transmission of Lei Shan Dao by my friend David Verdesi. In these photos you’ll see the hermit and Breatharian Xuan Kong who descended his cave to be with his disciple David Verdesi and students. You’ll see Jiang Feng, Xuan Kong’s main disciple and David’s teacher. You’ll also see me eating a root that was the food of the hermits (who ate northing else). In one photo I am doing Tai chi chuan in one of the peaks and in another you’ll see the sunrise. The last photo shows a piece of paper with a hole that was made by the projection of Qi from the hands of Grandmaster Xuan Kong who was standing 10 feet away. We had plenty of opportunity to meditate and practice our routines after the classes. Gonca Denizmen, a young model from Istanbul, led us through the contortions of Xing Shen Zhuang.

Nelson A. Navarro: In Memoriam

December 11, 1947 – September 22, 2019

(Read at the “Celebration of Nelson A. Navarro’s Life” held at the Kalayaan Hall of the Philippine Consulate in New York City on October 4, 2019)

show moreAlthough Nelson and I have the same surname, we are not related by blood. However, our ancestors – great, great grandfathers – came from Batangas. They were Chinese. Family name: Chan. Apparently, the Spanish Governor-General (perhaps Claveria? Nelson would know the name) issued an order to change the names of the Filipinos for purposes of the census. Nelson’s ancestor went South to Bukidnon, mine went North to Tarlac. Nelson is the godfather of my son Albert who was born in 1969. We were/are also fraternity brothers. I met Nelson in the mid-60s in UP when he was perhaps 16 or 17, a young sophomore finding his way in the university. Later Nelson and I were both involved, in different roles, in the First Quarter Storm, he as an activist and spokesperson for the Movement for a Democratic Philippines, me as a lawyer. I remember that he used to visit me in my apartment in Kamuning. We joined protests, along with Chito Sta Romana (now ambassador to China), Ericson Baculinao (for sometime bureau head of a media syndicate in Beijing) and a few other people who lost their lives in the struggle. I know Nelson so very well I could write a book about him.

AS WE CELEBRATE OUR FRIEND’S LIFE we have to promise to let him go, despite the strong desire to hold on to him, to keep him and the treasure trove of memories alive with us. We should remember that life is ephemeral, that in the Tibetan Buddhist classics on death and dying like the Bardo Thodol nothing lasts, we transition through the in-between, different stages through time, that ultimately death is liberation from the physical, that if we are lucky or if it is our destiny, we get reincarnated again to fulfill our karma on earth: somehow that’s something I would like Nelson to experience. We should also promise to look at Nelson with clear eyes and a balanced perspective because, like a lot of big personages who are larger than life, he was a multi-faceted man and we can be tempted to see him only from one angle or only from the bright side.

I should qualify my thoughts about him. We shared certain interests: literature, travel, politics, art. But we were also different. I am basically a man steeped in the eastern literature of the Tao Te Ching and the Bhagavad Gita, trained in the traditions of healing, martial arts, meditation, and quiet rustication , who pursued serenity and peace in in solitary contemplation while Nelson was a man bred in the culture of the west with its music, philosophies, and literature, the quintessential intellectual, passionately committed to learning more about History and its players, the issues of the day and writing about them, involved in the analysis of why certain events happened and what could have been done to alter their direction. To him, change was initiated in the world of action; to me change happened in tranquility, from within. Perhaps the truth lies between these opposite poles: we are transformed in our engagement with the external world as well as through our contemplation of the inner self.

I honestly believe he is one of the best Alphans the fraternity has ever produced — original, creative, productive, generous, protean, a shape-shifter, dedicated, thoughtful, authentic, brilliant, and in a good way, opinionated. I admired the man and his scholarship and embraced his genius and his idiosyncracies and achievements. He died at the height of his powers and at a time when his talent was in full bloom. If I had my way, I would have given him another decade or two on this earth for him to finish his work, and to find the peace and harmony that eluded him most of his life.

Last February I was surprised to see him waiting for me at the Asian Institute of Management café in Makati. He just showed up without calling ahead. He dropped by just to say hello; he stayed to talk for almost 3 hours. As usual, I just listened to him. That’s all one can do when Nelson starts talking usually non-stop. When he held court, he regaled us with these stories, details we did not know about famous people and our friends and history, obscure facts we were not aware of. His stories, collated through research and interviews over many decades, gave interesting twists to the ordinary lives of people and added color and definition to heroes and public figures and cast them in more human or more heroic portraits and scale or proportion.

He looked down on our country’s leadership, often exasperated and frustrated and angry that politics took this or that turn. It was obvious he loved our country and shared her sufferings and achievements with her. He was one of the few exiles who came back in 1986 leaving America and all its promise of a good life. He may have returned to the Philippines but was a New Yorker at heart: he loved Greenwich Village, Lincoln Center, the restaurants and cafes and the libraries and book stores, he passionately followed the operas, ballet and the symphonies and he returned to New York City, his true home, again and again.

He was extremely loyal and generous to friends, going out of his way to visit them and encourage them for their work. When he arrived in the US in 1972, we were the first family he visited. We lived in New Jersey at the time. Coincidentally that day I was driving to Chicago to pick up my 2 year old son Albert, his godson, who had also just arrived from the Philippines. So Nelson joined us on this long 2-day trek from Asbury Park to the Windy City up north. *One time back in the 1980s he got tickets for me and my 2 kids and we all went to a Richard Wagner opera, the Ring of the Nibelung, at the Met in NYC. We often attended the same Filipino events. We performed In the same shows, some of them just agitprop at LaMama ETC under the direction of Cecille Guidote. For some shows we wore bahags or loincloth and pretended we were Igorots. I choreographed fighting scenes and believe it or not, danced some numbers, including the role of Malakas to a 16-year old’s Maganda. Nelson was in the play “Ang Tatang Mong Kalbo,” Isagani Cruz’s spin on Eugene Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano. I remember the Hungarian coffee shop near St John’s Cathedral and the café in Greenwich village where we spent afternoons talking about our beloved Philippines that was in the grip of a brutal and predatory dictatorship, two expats homesick for their country, and dreaming of going home. We were both active in the anti-Marcos movement, we joined demos in NYC and Washington. we attended the same progressive DGs or discussion groups where we studied the literature of protest and revolution, and we wrote for expat publications, he for Loida Nicolas Lewis’ Ningas-Cogon, I for Philippine News. **

In the 1990s we hardly saw each other. For 10 years I lived in Boston to study acupuncture, Chinese herbalism and Classical Yang Family Tai chi chuan and got deeper into esoteric Taoism. He was in the Philippines writing books and doing commentaries on television with contemporary Jerry Barrican. LIke me, he traveled a lot.** For a long time I did not see him even when I returned to the Philippines to teach seminars on meditation, Qigong and massage. One day, at the Via Mare café in UP Diliman, I had dinner with Josue “Sonny” Villa, former ambassador to China, a childhood friend. It turned out Nelson was in the same restaurant with Ericson Baculinao, the old China hand and fraternity brother who had flown in from Beijing. So destiny brought Nelson and I together again. There we were, 50 years after we first met, Nelson and I were both aging seniors, silver haired and bearded, pale and wrinkled, miserably overweight, stooped and sadly limping – he from a stroke, I from injuries sustained in martial arts training and possibly old age.

No doubt he left his mark, he will be remembered … for his achievements no doubt, for a couple of his books possibly and his love for our country and people most certainly. I do not like to use the word hero to describe the man but he was definitely close to being one. We can truly say, he was one of a kind. That’s what the poet Du-Fu said of his friend Li-Po. It’s the best compliment we can ever pay a man.

I would like to close by reciting the mantra from the Heart Sutra, the Buddha’s sermon to his disciple Shariputra:

Gate, gate, paragate, parasangate, bodhi svaha! Translation: Gone beyond, beyond, to the Other Shore, everyone, Hallelujah!

Rene J. Navarro

*Martial law was declared three months later on September 21, forcing us both to remain in the US until 1986 after the fall of Marcos when we both returned home to the Philippines. He stayed in the Philippines, I returned to the US (in 1987) and trained to be a Taoist teacher and eventually study acupuncture and Chinese medicine in 1990. I kept my Philippine passport and citizenship and INS green card.

** Some of these essays – “The Last Days of Marcos,” “God Looks Down from Heaven,““Marcos Coliseum,” and “Jose Rizal: Zen Life, Zen Death” — appear in the Writings section of my website. There’s also my free English translation of Amado Hernandez’s “Kung Tuyo Na Ang Luha Mo, Aking Bayan” (from “Isang Dipang Langit”) in the poetry section. “Marcos Coliseum” was reprinted in Primitivo Mijares’ book Conjugal Dictatorship.

***He traveled to Machu Picchu, Egypt and China. So did I. I heard from Ericson Baculinao that he and Nelson went to Mongolia.

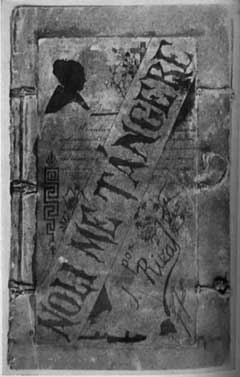

show lessJose Rizal: Alchemist

… the ultimate subject and object of the alchemical experiment (was) the alchemist himself. Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh, “The Elixir and the Stone”

… the true end of alchemy is not the manufacture of gold but the purification of the soul and the contemplation of god. Peter Marshall, “The Philosopher’s Stone”

Jose Rizal was a Mason but there’s nothing in the record to show what level he was. As far as I know, there’s nothing to show what he did as a Mason either. We can ask other Masons what they do but in all probability, they won’t say anything because the rituals are a secret. Rizal had many friends, in the Philippines and Europe who were Masons. Did he discuss Masonry with them? It is possible, but I have not seen any indication that he did. Perhaps somebody who has access to more of the Rizaliana materials could help me in my research.

show moreOne of the traditions and practices associated with Masonry is alchemy, the art of transformation that may have had its origins in Egypt, China or India. The word itself came from the root Alkemia, or black lands, the ancient name of Egypt. Alchemy was referred to later as Hermetic knowledge because the Greeks called Thoth, the Egyptian god of wisdom and writing Hermes. Alchemy was partly based on the Emerald Tablet, the sacred text that was attributed to Thoth. There are different versions, one of them in China. Some of its maxims are:

As above, so below. As below, so above.

What’s within is without; what’s without is within.

For every positive, there is a negative; for every negative, there is a positive.

These sayings underscore the system of correspondences and parallels between the body and the earth, on one hand, and the external world, on the other. If there’s divine in heaven, there’s also divine within. If there’s a feminine, there’s a masculine and vice versa. The art embraced a paradigm that included certain belief and concepts – nature and man as a manifestation of god, the possibility of perfection, of man being capable of reaching godhood. It is a system that established an ancient paradigm of reality and transformation.

We do not how it developed but in the course of its history, alchemy evolved a method for the transmutation of lead into gold, or the transformation of the raw human being into the perfect sage or magus. The process of alchemy was held as a secret, its “formula” was contained in esoteric symbols and images like sulphur and silver, Sun /Sol and Moon/Luna, Musculine and Feminine, Tiger and Dragon and the different elements like Earth, Fire, Water, Wood and Metal in China.

Alchemy itself started as a process of producing gold and immortality through the mixture of 4 different metaphorical elements: Earth, Air, Fire and Water or their equivalents. This was called external alchemy. In the course of time it became, as in China, a method of prolonging life and achieving perfection (internal alchemy), twin goals of the tradition. By finding the equivalent elements within the body, internal alchemy (also called Philosopher’s Stone) made it possible for practitioners to achieve perfection through the transmutation of energies and emotions. There are different paths or ways. In simple terms, the alchemy of Fire (Li) and Water (Kan) was able to produce “steam”, a higher element in the process.

Since the early 1990s, when I started studying Taoist internal alchemy, I began looking for evidence if Jose Rizal knew and practiced alchemy. His library contained books by Masons like Voltaire (Jean Marie Arouet). He associated with Masons like his friend Blumentritt. No doubt he was exposed to –- and was immersed in — the culture of the Enlightenment. But I did not expect him to mention alchemy, much less to talk about it of course because the theory and practice is considered a secret. Studying it without a knowledgeable master is dangerous and we are warned can result in mental derangement or death. It is evident that many of the symbols and images in Rizal’s poetry and the arguments in his writings, especially his correspondence with Father Pablo Pastells, were derived from the Enlightenment, the Hermetic transmissions, and Masonry and their vocabulary. For instance,

And when in dark night shrouded the graveyard lies

And only, only the dead keep vigil the night through:

Keep holy the peace, keep holy the mystery.

Strains, perhaps, you will hear – of zither, or of psalter:

It is I: O Land I love: it is I who sing to you.

Nothing then matters to place me in oblivion—

Across your air, your space, your valleys shall pass my wraith.

A pure chord, strong and resonant, shall I be in your ears:

Fragrance, light, and color – whisper, lyric, and sigh:

Constantly repeating the essence of my faith.

— Jose Rizal’s valedictory poem translated by Nick Joaquin

The verses suggest the destruction of the physical and its transformation into something subtle, energetic or spiritual. This is the essence of alchemy – dissolve et coagula. The transmutation of lead into gold, the gross human material into divine possibility.

“… in the light of the knowledge of the past and present, I weigh things, try to determine their causes and the finality of their activity, and strive to follow the direction they take. I see in everyone an inborn desire to know; I see the world outside full of colors, qualities and incentives that nourish this desire; I see misery as the chastisement of ignorance, well-being as the prize of knowledge. And I come to the conclusion from my humble reasoning that the Creator desires man to perfect himself by growing in knowledge.”

“Regarding the immortality of the soul and life eternal, how can I believe in the death of my consciousness, when everything around me tells me that nothing is lost but things merely change? If the atom cannot be annihilated, is it possible for my consciousness which rules the atom to be annihilated?”

— The Rizal-Pastells Correspondence by Raul J. Bonoan, SJ

Another poem is even more suggestive of Jose Rizal’s interest in and practice of alchemy:

Water and Fire

We’re water, you say; you’re fire.

As you like it, let it be!

We live in calmness,

And ne’er will fire see us fight;

Rather joined by wise science

In the burning seat of boilers,

Without anger; without rage.

Let’s form the steam, the fifth element.

Advancement, life, light, and movement.

— quoted from Pedro Gagelonia, Rizal’s Life, Works and Writings

It is clear that “the burning seat of boilers” refers to the laboratory that was used by alchemists to produce the Philosopher’s Stone. The poem points to the reconciliation of opposites – hot and cold, dry and moist – that is followed in all alchemical traditions, whether Egyptian, European, Indian or Chinese.

A prolific writer, Jose Rizal kept a meticulous and detailed record of his observations, thoughts and experiences. But sadly, in keeping with the tradition of Masonic secrecy, he did not bequeath us his method of alchemy, the path to human perfection.

The Last Days of Marcos

by Rene J. Navarro

Contemplating the ruins of his regime, Ferdinand E. Marcos stood frozen on the balcony of the palace. The waters of the Pasig River had never seemed so murky and polluted. His eyes scanned the faces around him. There were generals and presidential guards, cabinet officials and relatives, Imelda adherents and loyalists. And from the corner of his eye, Marcos caught a glimpse of the American ambassador with a military aide.

He wondered, Who had betrayed me?

show moreWhile the streets resounded with gunfire and the windows rattled from the explosions, Marcos searched the faces of those huddled about him for any sign of

deceit. Who could have been responsible for this coup? He was almost sure it wasn’t the military, for he had seen to it only his trusted lieutenants were in control. Was it his wife? But she was in New York since the week before – presumably occupied with her endless and extravagant shopping sprees.

Marcos quickly considered every name on his list. Not one of them could have had the temerity, much less the power, to initiate and pull this seizure through. They were all powerless. He had planned it that way. Could they have closed ranks secretly and decided on a mutiny? Impossible because he had taken care that each person in charge of a department or a bureau was hostile to and insulated from the others. Even the military was purposely fragmented to keep its generals from having any ideas. And his enemies – the radicals and progressives – were either in the mountain or in jail.

Meanwhile, masses of people armed with bolos, runs, sticks and stones, and molotov cocktails were marching, in union towards Malacanang. They came from different corners of Manila. Filling the streets with their numbers, they waved their weapons and their torches. Their chanting and footfalls drowned the sound of bullets in the distance. They marked inexorably closer until their united voices echoed through the deserted corridors of the palace.

As Marcos waited for the rescue helicopter to land, he vainly searched for that one renegade who had unleashed the storm.

A master tactician, Marcos had not anticipated the effects of recent developments – the bombings and selective assassinations and the demos in the streets. Ordinary citizens were marching, ready to face the powerful guns of the army. Students were again in the barricades with their pillbox bombs, molotov cocktails and, sometimes, guns and explosives. Many had died before international media coverage – and it focused world attention and drew pressure on the bankrupt and tyrannical regime.

The military had simply refused to confront the seemingly fearless and quixotic mobs after the first few weeks of bloodshed. Marcos thought that fear was enough to keep the populace silent; but, as more and more people were imprisoned, tortured and killed, and as life became more and more uncertain, the people became bolder, and they turned out of their hovels and tenements and joined hands with their comrades at the gates of Malacanang. No matter how many soldiers reinforced Mendiola, column upon column of slumdwellers, students, professionals, and all manner of men and women and children, came to fill the void of fallen comrades, and they could not be pushed back by armalites and grenades and smoke bombs.

Marcos did not also anticipate that the occasional bombings, which barely affected the workaday operation of the bureaucracy, would escalate into a systematic, orchesrated urban guerrilla warfare. At first, there were the small explosions in hotels and bazaars, which he dismissed as almost laughable. Later, after he was given fair warning, the explosives became more powerful and were planted in electrical stations, resulting in blackouts and partial paralyzation of the city. Government vehicles would stop in mid-traffic because either their engines were tampered with or the gasoline was diluted. There were more and more sabotage techniques employed by the shadowy urban resistance. Still later, when Marcos refused to abdicate, the underground escalated the pressure. He realized it was close to impossible to finger the suspects in the city and to round up the resistance members because, while it was comparatively easy to locate the mountain guerillas, it was very difficult to identify the urban underground. Guerrillas in the fields were fish in the ocean – drain the water and you catch the fish. But urban guerrillas were the ocean! Marcos understood and studied the modern rules of urban resistance from Cyprus to South America to Asia, and he knew well that a sophisticated city underground is almost impossible to contain.

As Marcos stepped forward into the waiting helicopter, he hesitated and took one last look at the assortment of people in the balcony and at the palace now dark and ghostly. He raised his right hand to wave a farewell but caught himself, turned and entered the helicopter door.

A few days before, he was comfortably in power, he thought. Meeting with his cabinet and his military leaders he assessed the political situation and decided there was no significant danger. He was assured the heat would just simmer down after the usual arrests and media announcements. Everybody he talked to said the situation was under control. But, as a precaution, he hastily and secretly sent his children abroad – just in case.

As the helicopter hovered over Manila, Marcos looked down and was seized with an undefinable anger. Who had betrayed me? he asked himself. He would, of course, issue the public statement to the media – that he was abandoned by the United States; that a communist clique had infiltrated the government; that he had served his country well….But right now, winging his way to the airport for that jet plane out of the country to his exile, he felt a sense of betrayal and, perhaps, self-pity. He was, finally, alone.

N.B.: While clearing my files, I found the article (a copy of the typewritten original is attached hereto) entitled “The Last Days of Marcos.” I think it was written in the late 1970’s and submitted to the Philippine News for publication. I don’t know if it was published.

In those days, we used to organize rallies and demos in front of the Philippine Consulate in New York or the United Nations, we used to write political analyses and satires, we used to gather to talk about the dictatorship.

Behind the major premise of the article was the belief at the time, held by many people, that President Ferdinand Marcos will not surrender his powers, that only some sort of armed struggle will work, that if he died, his heirs – Imelda and Bongbong – were there to succeed him. The elections of 1986, of course, led to his eventual defeat and exile. It wasn’t violence that did it but the united and peaceful will and determination of the people – the February Revolution.

Sometimes, we played the role of a prophet, we made predictions on how a person will die, we invented scenarios how a regime will end, who will win an election. History has a way of surprising us. Marcos himself did not believe that an election would result in his defeat or that the people and the army would revolt against him. I am sure that many people had predictions about Marcos. Mine is just one of them.

(First published in the Philippine News in 1982, this is one of the political pieces I wrote during the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos. I will reprint a couple more in the next few months.)

show lessPORTRAIT OF AN EXILE

Reynato Yuson, Greenwich habitué, expatriate writer and versifier, now on his nth unemployment check, had emerged, blinking, from the cluttered haven of the downtown eastside apartment he shared with the other Filipino bachelors, into the autumn sun. Clutching the satchel on his shoulder, he picked his way past the bushels of cabbages, yams and cucumbers on the sidewalk. The street outside the decaying Fillmore East Theatre had already burst with commerce and sounds on this early Monday morning.

show morePicking an apple along the way, he sauntered past the derelicts and Bowery bums, descended into the subway stop at Houston East, jumped over the turnstile as the doors of the train were about to close, and rushed in. He opened his bag and pulled out a manuscript of an essay on the Last Days of Marcos, a futuristic study of the dictator’s demise. Pen in hand, he made corrections on page one until it looked like the sketch of a wild bush.

He went down at the Grand Central Station, walked lazily through the harried commuters and up the steps past the Commodore Hotel sign, to the street drenched with rain. He scurried across into the New York Public Library, and quiet.

It was here we met to verify a matter that he had been working on rather enthusiastically, namely, the Wagnerian symbolism of Dr. Jose Rizal, the national hero of the Philippines. He suspected there was something uncannily similar in Rizal’s Noli and Fili and Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung. There were, he thought, too many similarities to be considered coincidental.

Reynato was at a friend’s apartment one night listening to the Ring Cycle with a libretto and an annotation by his side when it occurred to him that Wagner’s symbols and characters were oddly familiar. The story of the ring sounded

like the story of Maria Clara’s necklace or Simoun’s jewels. The fire symbol was like Elias’ immolation scene. Siegfried was like the noble Elias. Before he could finish Gotterdamerung, Reynato was holding, not the libretto of the Ring, but Rizal’s Noli and Fili, and was in an animated discussion with his host.

“I hope nobody has written about this,” he said to himself as he went through the index cards at the library. He admitted it was impossible to verify if any work has been done on the same theme, considering all the term papers and theses and dissertations decaying in some History or English Department.

He leafed through the diaries of Jose Rizal. Sure enough, Rizal was in Germany when Wagner was the rage of opera. But he could not find any indication in Rizal’s entries that he had listened to or knew about Wagner. Finally, Reynato reluctantly conceded that the similarities could be mere coincidence, that perhaps the parallel symbols occurred because they were universal. But he could not believe that Rizal thought of the immolation scene on his own. Reynato believed that Elias’ fiery death was new in Philippine literature. “It can only be explained by Wagnerian influence,” he said.

It was after one o’clock when, still unable to find confirmation of his thesis, he decided he needed more time and materials.

He walked to Times Square. He wanted to pick up a copy of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony # 2 (The Resurrection) conducted by Eugene Ormandy. “The one with Evelyn Mandac doing the soprano part,” he told the salesgirl at Sam Goody’s, as if this additional information would provide her with a further clue as to the record’s whereabouts. “And please get me Rampal’s ‘Sakura’,” he added.

Back at his apartment on the lower east side of Manhattan, we settled to a vegetarian brunch of yogurt and spinach omelette as the Rampal record played. While he boiled water for the herbal tea, I sat back to listen to Mahler’s 2nd. Reynato was quite curious about Evelyn Mandac’s performance whom he had heard during his college days at the University of the Philippines. Several times in the early 60s he had seen her at the Agnostic’s Inn, a carinderia owned and run by Dr. Ricardo Pascual , dean of the department of philosophy, after whom the place was named. But he had never talked to her even if sometimes they moved in the same circle because she looked solemn and forbidding. He liked her voice because it was edged with pain and vulnerability, a feminine quality that was elfin and oriental. He often heard her at the College of Law auditorium, where she was often invited to sing at the intermission of convocations. He concluded that her duet with Birgit Finilla was a powerful moment of artistry – they had two contrasting, but balanced, styles that gave the Mahler’s last movement a soaring, heartbreaking thrust into the triumphant choral finale.

Like somebody who wanted to probe the taste of his subject by dwelling on minutiae, I took a mental note of Reynato’s considerable record collection and minuscule library. He has the complete symphonies of Shostakovich and Beethoven; about seven or eight versions of Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto #3; a copy of the orchestral works of Revueltas; several Berlioz; Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concertos and Souvenir de Florence; a bunch of Japanese music for the koto and shakuhachi; two records of Maria Farandouri singing the ballads of Mikis Theodorakis; one by Suni Paz; several Cleo Laine and Red Army Chorus; Bach’s orchestral suite and Brandenburg Concertos; a few other classical records, prominently works of Brahms, Mahler and Prokofiev. His books included the collected poetry of Dylan Thomas, Eugenio Montale, Juan Ramon Jimenez and TS Eliot; the novels of Jose Rizal and James Joyce; the stories of Bienvenido Santos and Ninotska Rosca; the writings of Marx, Mao, Lenin and Stalin; a few Sartre and Camus. He also had an extensive literature on war (Clausewitz, Mao and Sun-Tzu), zen and Tai chi chuan.

Begging to be excused, after he served tea, Reynato lighted three joss sticks, bowed three times in front of an improvised altar with the statue of Guanyin, and put the smoking incense on a brass vase. It was then I noticed the enormous picture of Shiva dancing.

Reynato switched on a tape recorder and the small apartment was filled with Indian music: sitar and table with chanting in the background. He sat in front of the altar, twisted into a full lotus posture and assumed an attitude of meditation.

As the afternoon deepened, I realized one fact about this man. He did not betray it, but he was quite homesick for his country. He reminded me, as he drifted into inner space, of certain characters from the fiction of Bienvenido Santos and Nick Joaquin. He may be listening to Beethoven or Japanese koto music or, like now, to the staccato rhythm of a Hindu ritual, but he is realy imagining that he’s back home – or escaping from the unreality of America. He may be at the beach watching the ocean or the sea gulls, but he’s actually dreaming of his homeland. His attachment to the sea, I suspect, is a well-disguised nostalgia for islands far away.

But he can’t go home yet – or he refuses to go home – although the prospect of again walking the streets of Manila tantalizes him. Like Joaquin’s exile, he’s waiting for his country to be free. He keeps on searching for reports on the successes of the underground movement and the defeats of the dictatorship. Often his moods are determined by the developments in the Philippines. Is there news of Marcos’ ill-health? Reynato celebrates. Is there a new wave of tortures and arrests? He becomes upset.

Born at the foot of Mount Arayat, he was able to observe the underground at close hand. He remembers the times, in his childhood, when peeping through the window, he caught glimpses of armed men moving silently along the barrio trail. Growing up at the edge of town, he had become familiar with the cadres – they would drop in to talk; and he noticed the rifles that glinted in the dusk. But times there were when bloody bodies would be paraded through the streets in a native sled and dumped in front of the town hall. Reynato would run the dusty mile to see them. Attempting to identify the faces, he found the carcasses unrecognizable from the bullets that had smashed the bones and flesh.

Reynato learned from the teach-ins conducted by the cadres in his hometown that there was a guerrilla war. Which brings me to another aspect of his exile: he feels guilty for being in America. “We should be in the mountains of Sierra Madre wielding armalites,” he says. Somehow, in the wave of the 1960s he fell in with relatives who had filed applications to migrate to America. When his papers were finally approved by the US Immigration and Naturalization Services, he had become involved with the vociferous and militant student movement in Manila. Given a couple of weeks to leave as an immigrant, he decided against doubts to book a flight. Late in 1970 he found himself in New Jersey with cousins who had offered to take him in, in the meantime that he was looking for a job.

But he regretted his decision to leave the Philippines as soon as he stepped on the plane.

When he was advised by a fraternity brother in the military to stay in America because there were orders for his arrest in 1972, he felt a little relieved. At this point, he vowed to write of the situation back home and the liberation struggle of his people.

Thus began another phase in his life. For he had never considered himself a writer. He had settled early on to become an accountant. Going to college in the late 1960s he came under the influence of certain members of the Kabataang Makabayan. He joined teach-ins. He watched the Kamanyang Players, a political drama collective. He went to a few demos. He read the works of Renato Constantino and Jose Ma. Sison. Somewhere, in the process, he was politicized.

“It was on one May Day march that I really underwent a change,” he admits. “We gathered at the boundary of Manila and Quezon City, at that circle where so many demonstrations began. Waving flags and banners we marched through the streets of Manila, along the university belt, past Quiapo, to Congress, where we stopped to listen to speeches. Eugene, Raquel, Gary, Julius, among others, were there. While we were all gathered, I joined a friend who was working with a senator to pick up some papers from his office. As I walked along the corridors on the third floor of the congressional building, I saw soldiers aiming their high-powered rifles at the demonstrators in the street. I could not believe my eyes. Later, while on a sit-in with strikers at the US Tobacco Corporation near Bonifacio Drive, we were trapped by the military in that small alley. From both sides, they came, their guns cocked. We were completely surrounded, and helpless. It was then I realized the truth of the adage that political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.”

Now, in America, not having taken up a gun, he has taken up a pen (a ballpoint pen really). “It was a difficult education,” he says. “There I was, an expert on numbers and, suddenly, I decided to string words. I read a lot: James Joyce, Nick Joaquin, Sartre, Camus, Dylan Thomas, Malraux, Hemingway. It was an agony to write but I had a valuable ally: my imagination. As a child, I sat at the feet of my grandfather who told me stories from native folklore and corridos.”

While his work is not known for its literary merit, it reflects that imagination. Such satires as Marcos, Inc., Marcos Coliseum, The Assassination Attempt Revisited, God Looks Down from Heaven, to name a few, are an exercise in fantasy. Reading them one detects that unmistakable flight of fancy, that hint of humor, forcing one to conclude that somewhere in that biting indignation and trenchant style is a child retelling the stories he had heard from his grandfather.

“My writing is intuitive. I don’t aim to achieve literary or journalistic excellence. I express my anguish and my joy,” he says.

At this point he feels he has exhausted the medium of the political satire. He’s itching to write a novel about an exile (semi-autobiographical, I am sure) who had an itinerant Batangueno for a great-grandfather and a Pampangueno for a grandfather (a former member of the wartime guerrilla movement called Hukbalahap). He’s als planning to to write a play – “ a didactic one along the Brechtian mold, which will deal with the moral questions facing a revolution, and will center on the death of Andres Bonifacio.”

But he complains of not having enough time. “Too many engagements, too many preoccupations,” he says. “I will go crazy if I don’t see plays and museums and concerts.” With his girlfriend, of course, whom he refuses to identify. “We’ve grown together intellectually and emotionally. We’ve weathered a lot of crises in America. But we’ve survived, together. We’ve shared a love for certain writers and composers, especially at the beginning of my apprenticeship as a scribbler. She introduced me to books and classical music. At the start, I could not tell the difference between Beethoven and Mahler. I went for the schmaltzy romances of Mantovani. But unfortunately, it’s coming to an end, this relationship, because she wants to get married, to a Jewish doctor. She wanted to continue our friendship. We’ll still go to concerts and museums together and you can visit me, she said, but I don’t think I’ll see her again because I’m not too sure she can stand the gossip that usually hounds even a platonic relationship of a bachelor and a married woman or, for that matter, of a married man and a single woman. I don’t think she should take the risk because there are too many aggravations. And the Filipino community is not famous for its tolerance. If anybody sees us attending a play together, she’ll be the talk of the town. It would be nice to share a friendship with a woman of her humor and intelligence, but.” Here his voice drifted wistfully and his eyes wandered about restlessly.

It has not been an easy break-up for him. For his commitments are strong and emotional. To cheer him up, on his 30th birthday, a few mutual friends (identified here only by their nick names) gave him a surprise party. Angie prepared a dish of crispy fried duck and spicy string beans. Nelson cooked one of his giant omelettes. Tanya flew in from California to add the honor of her presence to the occasion. Ching whipped up her delectable sinigang na sugpo. Elvi prepared her chicken relleno. Loida, heavy with her second child, brought a bottle of Chablis. Poch graced the festivities with his professorial mien. Rev dropped by, greeted the honoree, sat in one corner and ogled at the girls. Mike came with his ubiquitous guitar. Sonny brought his justly famous chicken estofado de Cagayan. It was a happy event for everybody except for the celebrant. He brooded endlessly even if everybody commiserated with him.

Terribly moody, Reynato has a vulnerability about him. His spontaneity makes him an easy target for jokes and intrigues. “My reclusiveness is my defense,” he confesses. An admirer of Exupery’s The Little Prince,” (of which incidentally he has versions in English, French and Spanish, and records by Peter Ustinov and Richard Burton), he adheres to the credo: “It is only with the heart that one can see. What is essential is invisible to the eye.” (Actually, he said this in Spanish, a rendition which he thought sounded better than the English or the original French.) He is also fond of saying, “You are responsible for what you have tamed.” (He said this line in French, which he considered better than both the English and Spanish translations.)

As I write these lines, Reynato is having another “agenbite of inwit” – a description from James Joyce he tells me –which means I presume a seizure of guilt. He wants to go home. Despite the icy winter weather, he goes to the beach more and more frequently. He would take the train to Long Beach or Far Rockaway in the morning, stroll stroll along the shore, do his tai chi chuan several times, and catch the train back to Manhattan. I can imagine him as he walks on the beach, his eyes constantly drifting to the horizon and the hazy sun. No, his mind is set not on the scene but beyond 10,000 miles away where his country is in the grip of a crisis while he is out here scribbling satires or weaving nostalgias.

Often I wonder if he should go home or if he has already gone home. He is so much a part of émigré propaganda literature I can’t conceive of him not writing for Filipino periodicals whatever his excuse or wherever he may be. At the same time, his guilt trips are profound and disturbing, I am afraid he would become pathologically melancholic.

If and when he goes back home, what would he do? Live in the old hometown of Arayat? Or work in Manila as an accountant? Considering his background, would he go to the hills? I have not asked him these questions but they weigh heavily on my mind.

There are times when I have an image of him in the middle of a demonstration in Manila. While he sympathizes with its tactics of a protracted war, he has chosen not to join either the NPA because, being a free spirit and an unfettered mind, he has found it impossible to abdicate his freedom for something he considers intellectually elusive, or the Democratic Socialist underground because he considers it a basically elitist improvisation. He is essentially a writer of the human condition; therefore, he would cast his lot with the downtrodden without committing himself in an ideological box. I can picture him: he stands side by side with the slum dwellers of Tondo as pillboxes and Molotov cocktails explode about him. A smoke bomb whistles in front of him as the Marcos mercenaries force the crowd from the gates of Malacanan. Finally a shot rings …

The thought he might get killed has occurred to me, it is true. As one who has been involved in the student movement of the 1970s, I know the risks inherent in street radicalism. I also know the fascist soldiers of the New Society would not have the scruples or respect his noble dreams or his frail body. It is a morbid thought, to be sure, but having known him so closely, I feel anxious for his life. He is not, after all, just another number in the struggle as far as I am concerned. Perhaps., again, my anxiety may be due to my own memories of mangled bodies exhibited by the military on the steps of the plazuela in Tarlac, of demonstrators mowed down in the streets of Manila and of comrades tortured mercilessly in the Philippine prison camps. Even today, in my sleep, I am haunted by the eyes of a friend whose genitals bore the marks of an electric wire and whose back was permanently scarred with the imprint of an army knife.

Nevertheless, while I hope for his safety, I can understand his obsession to return. Whatever happens to him there would be a lot better than for him to be run over by IRT subway express or shot by a desperado in Central Park. I can also understand his existential search for meaning – that defiant affirmation of self against the fatal negation of an absurd universe.

If he chooses to find fulfillment in action, he cannot be faulted. For, as an exile twice over, his loneliness is more profound, his sense of absurdity deeper, and his dread more painful than Sisyphus’. It is possible he may find that lost humanity in the barricades or in the camaraderie of the committed or even in the earthy sweat of the urban proletariat. It is also possible that he may discover that intense union of mind, body and spirit when the psyche is least fragmented in the classic confrontation with the Enemies of the People. I hope he would find success where I, sad to admit, have failed.

I have not seen Reynato Yuson since our last interview. But reading the Philippine News, I can see that he is alive and well, living in Manhattan and up to his old tricks.

Somehow, as I close this brief sketch, I entertain the hope he would not read it. He is a very reclusive chap and will probably be embarrassed to read an article about himself. He allowed this travesty and invasion of his self-imposed and well-guarded hermitism only with an assurance that his mug shot will not be used and that no impertinent physical description would be made. He has tried to maintain his anonymity all these years under the guise of pen-names. On impulse, in a rare display of daring, he consented to an interview and, despite doubts, opened himself to scrutiny and exposure.

He is not the type to hang around the phone or attend socials. In Gotham he would rather have dinner with a friend, listen to a new recording or cuddle in bed with a book. A tai chi chuan student he would practice alone every day and get high after the third set; but he is not a martial artist in a strict sense because he would go through the regimen not for combat but to be in tune with the universe, to achieve satori and improve his sexual prowess. He is also wont to descend on bookstores for that rare tome or print. On summer nights, when the heat is oppressive, he would walk either to the esplanade overlooking the FDR drive and the Queensboro Bridge or the Brooklyn Heights promenade facing the Manhattan skyline and, unafraid of the muggers the city is famous for, watch the lights in the distance.

Whatever, he is the quintessential urban loner. If he had a chance, he would probably repair to some desert cave or a mountain monastery to contemplate his novel if not his navel (or both). He avoids company if he could help it because he finds most New York conversations hypocritical and wasteful. Corollary to this bias is his preference for physical contact which he finds more direct and satisfying than words.

If only he had the transportation, he would take a dear friend for a drive to Long Island, via the Southern State Parkway, exit for the Robert Moses Parkway, and go south, past the verdure of Belmont Lake, into the open plain, where the road leads to the awesome bridges spanning the waters of Oyster Bay, from whose promontory they could glimpse a view of the islands on the right and the leisure yachts beneath, and on to the shores of the Atlantic, where alone they would walk hand on hand, pushing a clam with bare toes here and there among the wet sands, watch the sunset over Manhattan and, listening to the endless roar of the sea and the shrill cry of the seagulls overhead, dream of his colonial country where at the moment a war of liberation is being waged against a fascist state while he awaits the end of his exile in the metropolis torn between a mixture of emotions — the need to withdraw from the crowd, a desire to write and the compulsion to return to his ancestral home.

By Rene J. Navarro

Malverne, LI, NY 1982

LIBAI’S CROSSINGS

Weston, Massachusetts

It was going to be a rather long

journey but not long enough.

I had not gone home

to the Philippines in 6 years.

I wanted to stay

for a while.

I have been uprooted

so many times, there’s really no home

to speak of, not in Asbury Park, New Jersey,

not in Malverne, Long Island, not Pburg,

New Jersey, not in Lake Harmony,or Easton,

Pennsylvania, where I lived

for a longer time.

For the expat, home is

where he is. Afraid and tired

of moving, some don’t even unpack

anything, except what they need

for their job or daily living.

A journalist in Singapore

had a number of foot lockers

which she never did empty,

except for a few clothes

that she wore to work and sleep;

she had no books, except what

she loaned from the library

or friends. They follow the trail

of employment, wherever

it will take them.

I was for 2 years in Neptune, New Jersey

when I first migrated. Then Albany

corner Winthrop, Brooklyn, just across

from the drug addiction center: four

years. And Long Island: 6 years. And back

to New Jersey again. Like migrant

workers who stay

for the season, and then move on.

I wanted to see Bamban,

where I was born,

the only place to which I truly feel

a sense of connection although my family

and I left when I was 11 or 12 years old.

It was buried in lahar

from the volcanic eruption

of Mount Pinatubo. I wanted to see

my relatives, especially

the old uncles and auntie whom I may not

see again.

I missed my Shaolin/Buddhist martial arts

master, Johnny Chiuten; he had not written

to me for years, not even a Christmas

card. Last time I saw him,

he had a triple by-pass surgery.

It was in New York in early ’89,

and he could not really move

around much or eat.

I used to train under him

in the ’60s. We studied Tai Chi Chuan

together in Manila’s Chinatown.

I saw him a few times in Bantayan,

a tiny island off

the northwest tip of Cebu province

in central Philippines.

where he had retired

to run his family’s

bakery.

I also wanted to visit Lao Kim,

Johnny’s old teacher, and mine too,

who was in Kowloon. Eighty-nine

years old last time I saw him, frail

and going blind, shuffling his way

across the small one-room space

of his 27th floor flat.

At 54, I was suddenly more aware

of getting old. It was a realization

of mortality, not just of myself,

but of everything

that I know and remember,

that brought me back for one more visit.

Something you do not expect:

a sense of time running out

when you see others

and yourself

getting sick.

I booked my flight more than a month

in advance. My travel agent

in Weston was supposed to make

some changes in my itinerary

(a few more days in Korea, for instance)

but two days before my departure,

I was told she wasn’t working

at the agency anymore. The new

travel agent told me

in so many words that I couldn’t change

my itinerary at all, that I got some

kind of economy package, I had to stick

to it or else I had to pay a lot more.

I thought she did not really

know, she was trying to scare me

so that I won’t

force her to do any more work.

I should have suspected when

she could not tell me if I needed

a visa to China that Asia

wasn’t her turf. It was one

of the first bad omens

of my trip.

The thing is not to be upset

when something like that

happens. Consider it as part

of the adventure. You just have

to bear up to them. Next time

get a travel agency that knows

the route that you are going

to take. It’s great to give

advice like this

in retrospect, but at the time

I was furious and ready to hang

her by her toes.

My mother asked me to bring

some canned goods/corned beef for my brother

in MetroManila. I vigorously refused

saying that I wasn’t going to lug

a box of Libby’s Corned Beef across

two continents

and an ocean for anybody,

not even for her. What is it

about the Filipino’s fondness

for carne norte anyway? A G.I.

legacy from the postwar, it’s

expensive, unhealthy and colonial.

When my dentist heard

that I was passing by Seoul,

she advised me to see her best friend

— I was not asked but I thought

a pound or two of decaffeinated organic

coffee was an adequate gift.

Kim, my Tai Chi friend, asked me

to see his wife and wanted me

to give her some cosmetics

— and if you have a problem

with accommodations just tell her,

she has a room to spare, he said.

It’s the curse

of traveling — you have to spend

part of your time being

a messenger

and a parcel delivery

man. Did Libai/Lipo,

my friend from the Tang Dynasty,

ever worry about transporting

a box of dried dates for a relative,

from place to place?

I thought I couldn’t catch

my early dawn flight

from Boston. Two toll booths

on the Mass Pike wouldn’t

let me through.

My housemate, who took me

to the airport,

couldn’t believe it either.

Why is it things like that

happen when you are in a

particular hurry?

You want to travel

on vacation? Get ready

for something to go wrong,

if not on the road

or the plane, then at customs

or immigration.

Seoul airport was a bad sign, too.

My made-in-Japan camcorder

was confiscated by Korean customs.

Perhaps it was due to a misunderstanding.

The customs man spoke only Korean,

I spoke only English. Fortunately,

my friend Kim’s Korean wife

Eugene met me at the airport.

She interceded in my behalf

until Customs, after filling

up all those forms and blaming me

for the episode, gave me

back my camera. It’s modern

travel: you zip through

time zones and when you land

you are in a different culture.

The old-time hoboes,

I am sure, did not have to deal

with language barriers as much

since they moved within

their own

nation.

The night wasn’t over

yet. I had to see Sarah,

my dentist’s friend,

at the Dragon Hill Inn

in a US military base.

She was supposed to reserve

a room for me. When I arrived,

she was already waiting

for two hours, she had given up

on me, and was ready

to leave. It was quite

a warm welcome she gave.

She screamed my name and gave me

a bearhug. If she were stronger

she would have lifted me in the air.

I was quite happy to see her really

but I couldn’t help

but feel self-conscious

about it. Imagine

the scene: at least 50 Americans

waiting for a taxi were

watching while a young

blonde woman wearing camouflage

uniform, complete with a cap

and polished boots, gave an ear

-splitting welcome to a bearded

Oriental.

There was no room at the Inn

but one was available

a mile away in another military

hotel.

Far from being a tropic

country, Seoul was very cold,

colder than Boston.

Southerly winds

bringing the frost

from the Siberian

desert up north

that chilled the bone.

Sarah and I went slumming in Itaewon,

Seoul’s bargain shopping district

near the US military base.

I’ve been to Itaewon before (in 1988)

to buy a few things — a replica

of an ancient bell (for its sharp,

sonorous, mournful sound and elaborate

dragon design); some cushion covers

with variations on the Tai Chi symbol;

and a few crystals (Pa-Kua and pyramid

shaped). I recommend Itaewon

to those who are interested